Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Renewal Policies as States Prepare for the Unwinding of the Pandemic-Era Continuous Enrollment Provision

Tricia Brooks, Allexa Gardner, Peyton Yee, Jennifer Tolbert, Bradley Corallo Follow, Sophia Moreno, and Meghana Ammula

Published: Mar 16, 2023

In the third year of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), Medicaid enrollment continued to increase albeit at a slower pace than in the first two years of the coronavirus pandemic. Since March 2020, states have provided continuous enrollment in Medicaid in exchange for enhanced federal funding. This continuous enrollment provision and enhanced federal funding were originally in place until the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). In December 2022, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (CAA) delinked the provision from the PHE and ends continuous enrollment on March 31, 2023. Beginning April 1, 2023, states may restart disenrollments after conducting a full review of eligibility. States that follow all federal Medicaid renewal requirements, take steps to update enrollee contact information, and attempt to reach enrollees via non-mail modes before terminating coverage for returned mail will qualify for ongoing enhanced federal funding that phases down until the end of 2023. States must also report to the federal government specific data needed to monitor the impact of the unwinding or risk financial penalties for not doing so.

As states begin to “unwind” the continuous enrollment provision, many people will likely be found to be no longer eligible for Medicaid. Others could face administrative barriers and lose coverage despite remaining eligible. Existing state enrollment and renewal procedures, as well as state approaches to the unwinding of the continuous enrollment provision, will have major implications for Medicaid enrollment and broader coverage. Some states are prioritizing maintaining coverage by implementing the unwinding more slowly and taking steps to make it easier for people to renew coverage, while others are emphasizing a quicker end to continuous enrollment that reduces budgetary costs.

The 21st annual survey of state Medicaid and CHIP program officials conducted by KFF and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families in January 2023 presents a snapshot of actions states are taking to prepare for the lifting of the continuous enrollment provision, as well as key state Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies and procedures in place as of January 2023. The report focuses on policies for children, pregnant individuals, parents, and other non-elderly adults whose eligibility is based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) financial eligibility rules. All states and the District of Columbia responded to the survey, although response rates for specific questions varied.

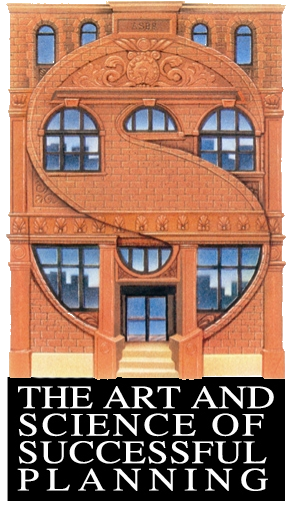

State Policies and Actions Can Promote Continuity of Coverage During the Unwinding Period

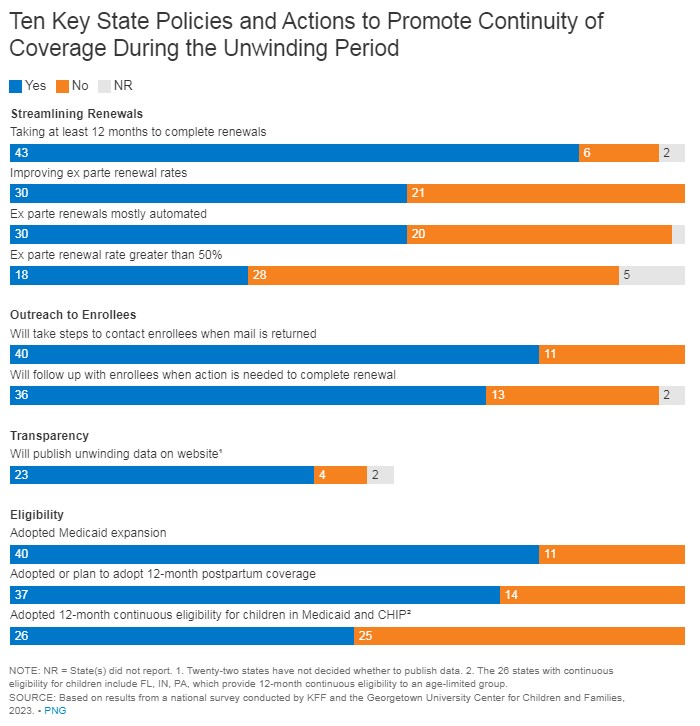

Leading up to the end of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision, CMS has issued guidance and granted states certain flexibilities designed to promote continued coverage during the unwinding period. We have identified ten key policies and actions that could affect continued enrollment in Medicaid. These policies include taking 12-14 months to complete renewals following the end of the continuous enrollment; taking steps to increase the share of ex parte renewals and completing more than 50% of renewals using ex parte processes; following up with enrollees when action is needed to complete a renewal, attempting to contact enrollees when mail is returned; and publishing comprehensive unwinding data on the state’s website. In addition, states have other policy levers, such as adopting the Medicaid expansion, extending 12-months postpartum coverage, and providing 12-months continuous eligibility for children that can also increase the number of people who will be able to retain coverage. State adoption of these policies varies. In states that are planning to move more quickly to complete renewals, have lower ex parte renewal rates, do not follow up with enrollees who have not responded to a renewal request, are less transparent with unwinding data, and have not adopted the Medicaid expansion or 12-month postpartum coverage or continuous eligibility for children, the risk of coverage loss during the unwinding period is higher, though budgetary costs from continued enrollment will likely be lower.

Plans and Preparations for the End of the Continuous Enrollment Provision

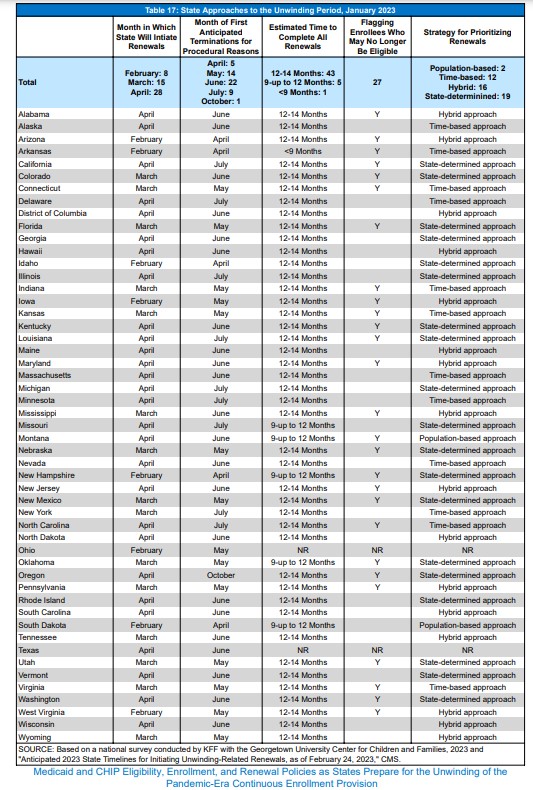

Most states are waiting until March or April to initiate their “unwinding” plans and plan to spread renewals over 12 to 14 months. States may start the unwinding process by initiating the first batch of renewals in February although they may not disenroll anyone before April 1. However, more than half of the states (28) are waiting until April to begin the process with 15 states starting in March and eight in February. Most states (43 of 49 reporting states) plan to take 12-14 months to complete the unwinding process and return to routine operations. Taking more time to initiate and complete the unwinding process can help to avoid overwhelming staff resources and prevent inappropriate terminations but could maintain enrollment for potentially ineligible people for longer.

More than two-thirds of the states (35 of 49 reporting states) are adopting an approach to prioritizing renewals that considers multiple factors, including time since last renewal and potential ineligibility. The approach a state chooses will determine how renewals are sequenced for various groups or cohorts. Using a hybrid or state-determined approach gives states greater flexibility to target potentially ineligible enrollees early in the process while delaying action on vulnerable groups or enrollees whose eligibility is unlikely to change. Fewer states (12) are adopting a time-based approach, which generally schedules renewals based on application or last renewal date. Only two states are taking a population-based approach that processes renewals by eligibility groups or cohorts.

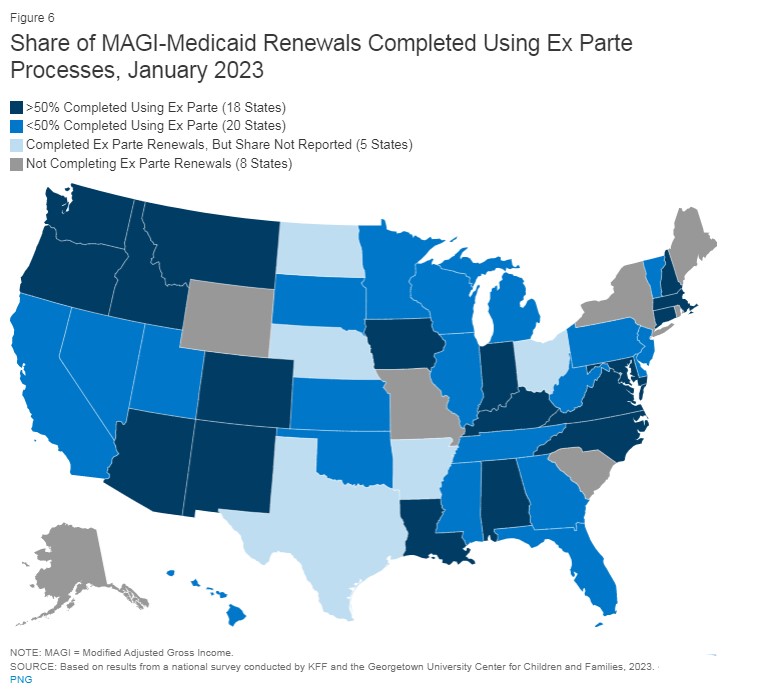

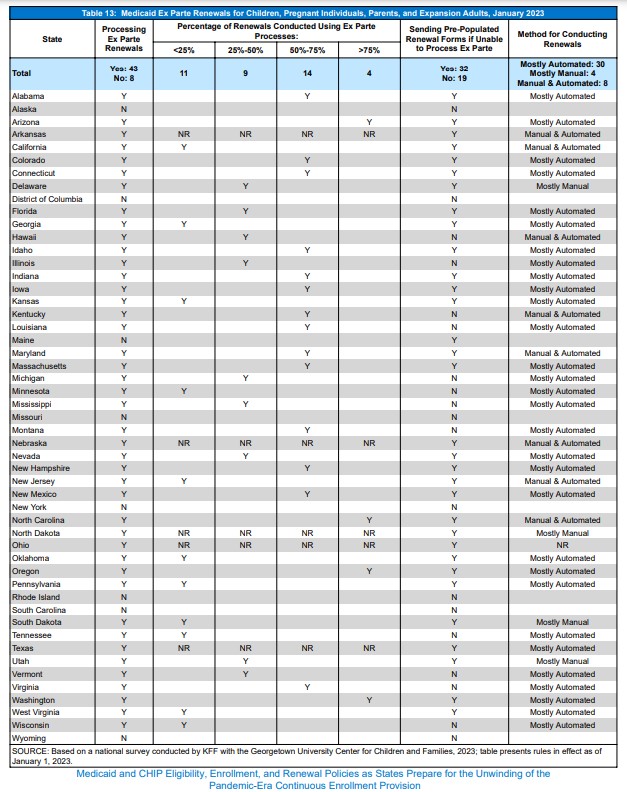

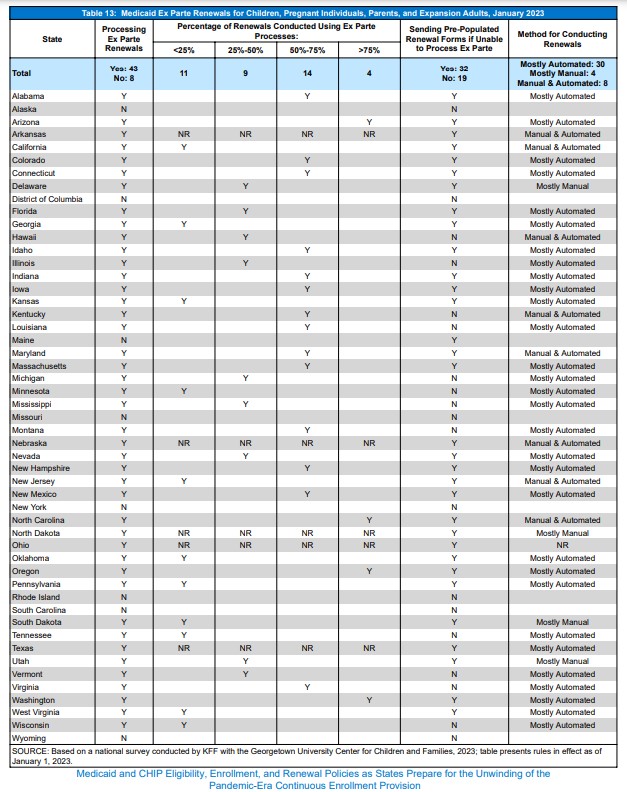

A majority of states (43) have continued to process ex parte renewals over the past year. States are required to first try and complete renewals through ex parte processes by using reliable data sources to verify ongoing eligibility. Ex parte renewals reduce administrative burden on both states and enrollees and can lower the number of disenrollments that occur because an enrollee is unable to complete the renewal process. Among states that are continuing to process renewals, 32 states have also continued to send prepopulated renewal forms when the enrollee’s eligibility cannot be confirmed via ex parte.

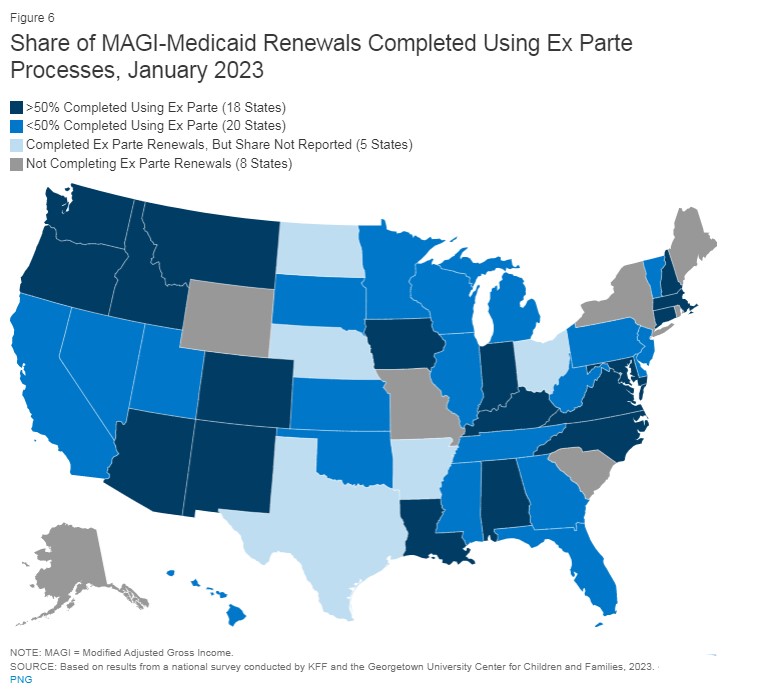

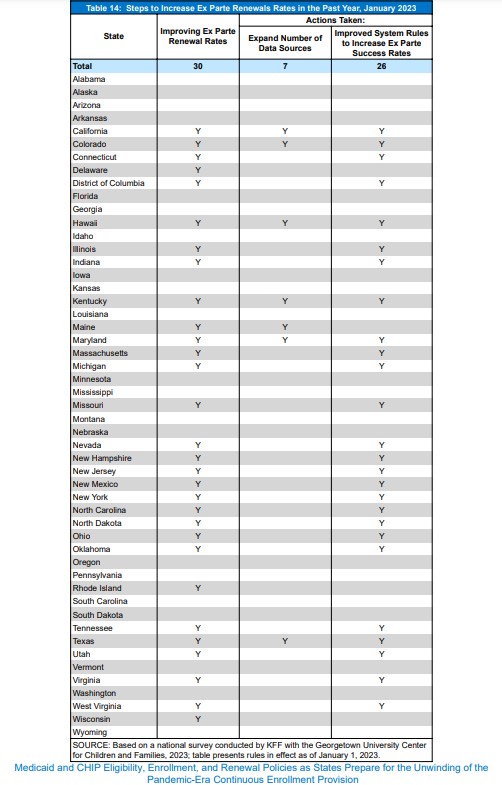

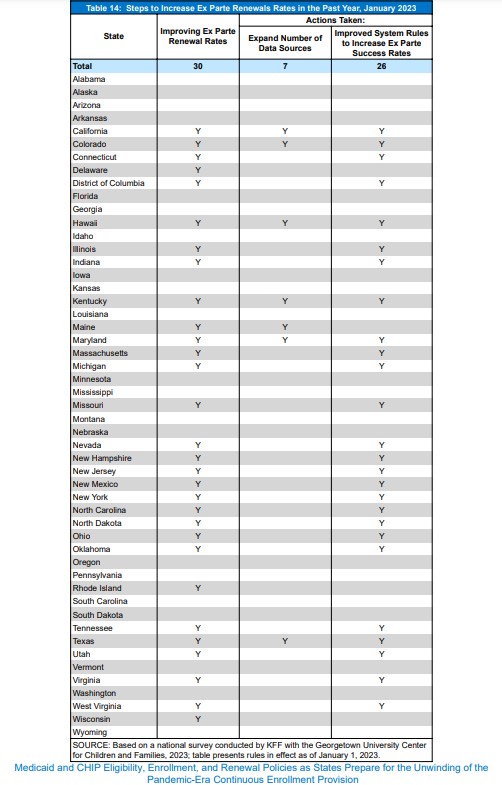

Over half of the states (30) have taken steps to increase the share of renewals completed via ex parte. Achieving a high share of system- and data-driven renewals increases administrative efficiency, allowing eligibility and call center workers to concentrate on complex cases. However, it may require investments in systems upgrades that can be costly for states, even with enhanced federal funding available. Actions taken to increase ex parte rates include enhancing system programming rules and expanding data sources. Of the 38 states reporting ex parte rates, 18 states are successfully processing more than half of renewals using ex parte processes, up from 11 states in 2022.

About half of the states (27) have been flagging individuals who may no longer be eligible or who did not respond to renewal requests, including six states that are conducting data matches to identify these individuals. States that have continued processing renewals have been able to flag individuals who they have confirmed are no longer eligible or appear to no longer be eligible, although not all states have done so. However, only a small number of states indicated that they plan to prioritize renewals for “flagged” enrollees early in the process.

Among the just over one-third of states able to report, they estimate that about 18% of Medicaid enrollees will be disenrolled when the continuous enrollment provision ends. However, the estimates range widely across reporting states from about 7% to 33% of total enrollees. This estimated average disenrollment rate is slightly higher than the 13% reported by states in 2022, although it is consistent with other estimates indicating about 15-18 million people may lose Medicaid coverage over the coming year.

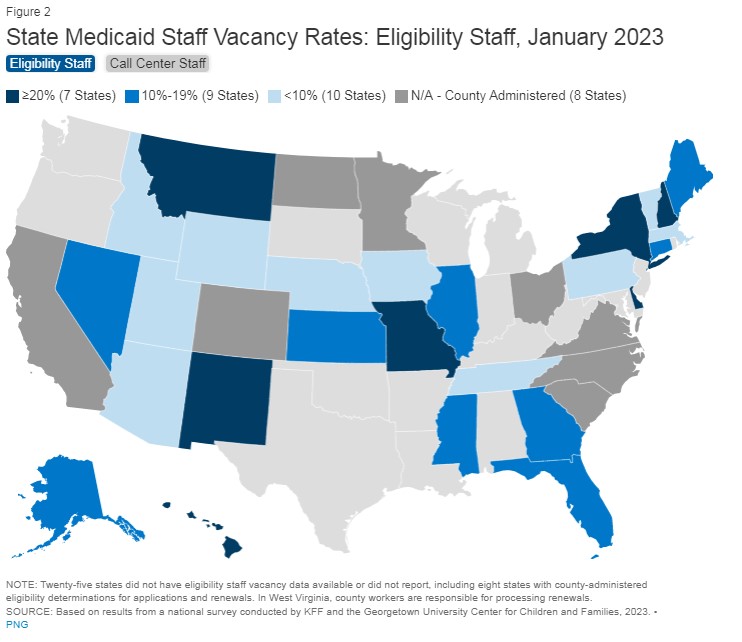

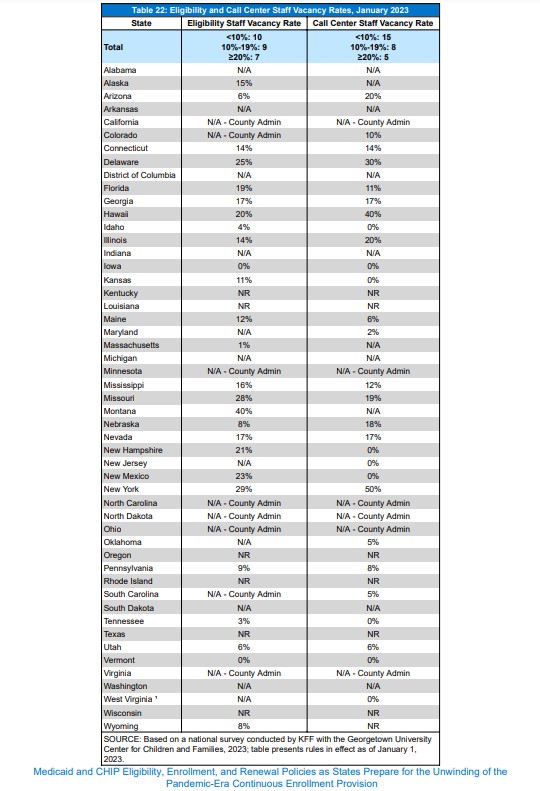

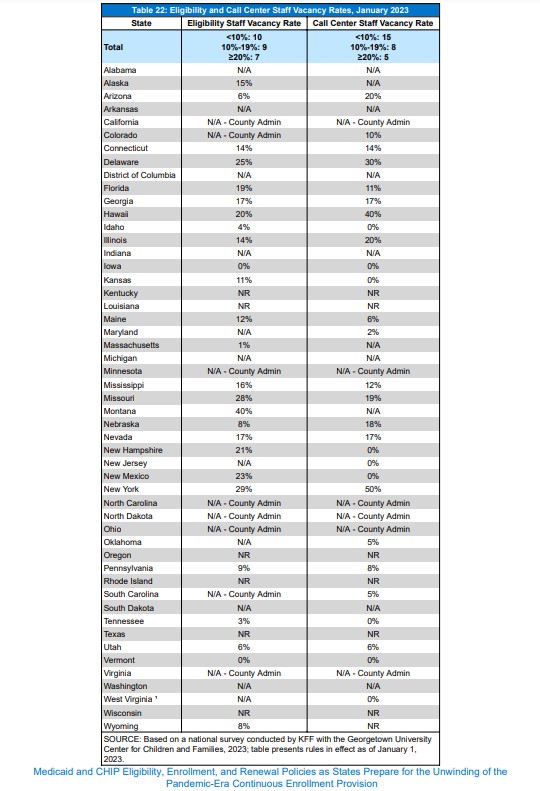

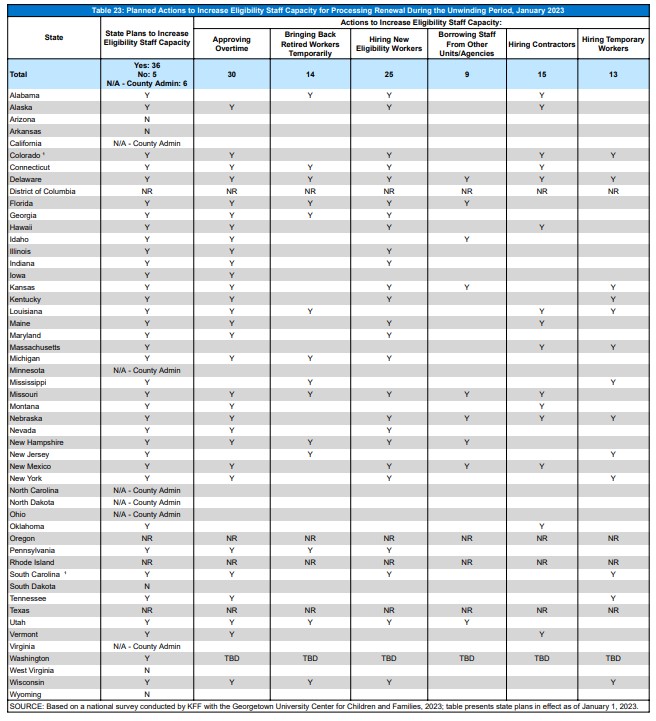

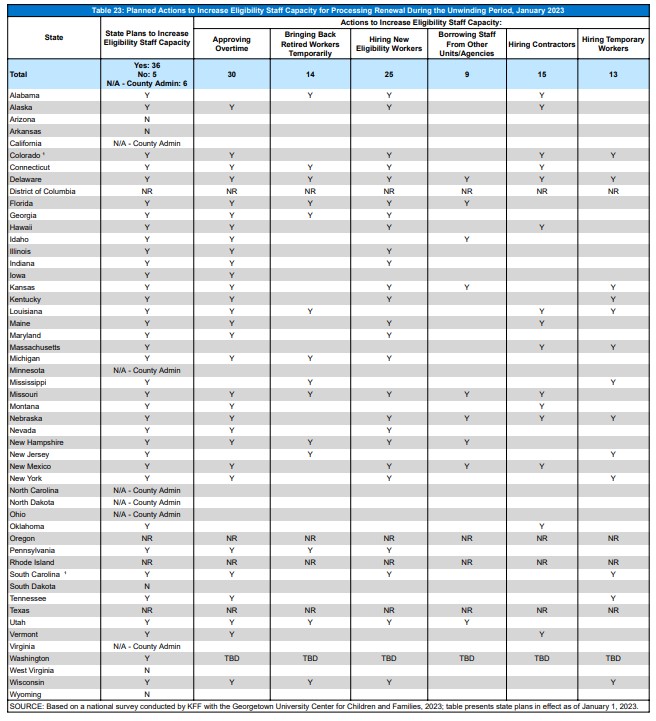

The unprecedented volume of work ahead comes at a time when most states face significant staffing challenges. More than half of reporting states have staff vacancy rates greater than 10% for frontline eligibility workers (16 of 26 reporting states) and slightly less than half for call center staff (13 of 28 reporting states). States are adopting multiple strategies to address eligibility staffing shortages, including approving overtime and hiring new staff, temporary workers, or contractors. It is less clear what actions are being taken to boost capacity in the nine states that rely on counties to conduct renewals, although several states noted that they are providing additional resources to counties to boost staff capacity.

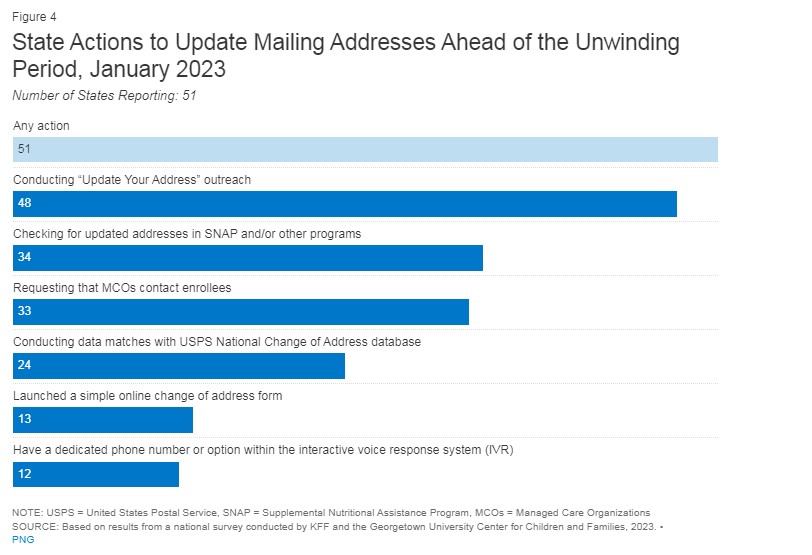

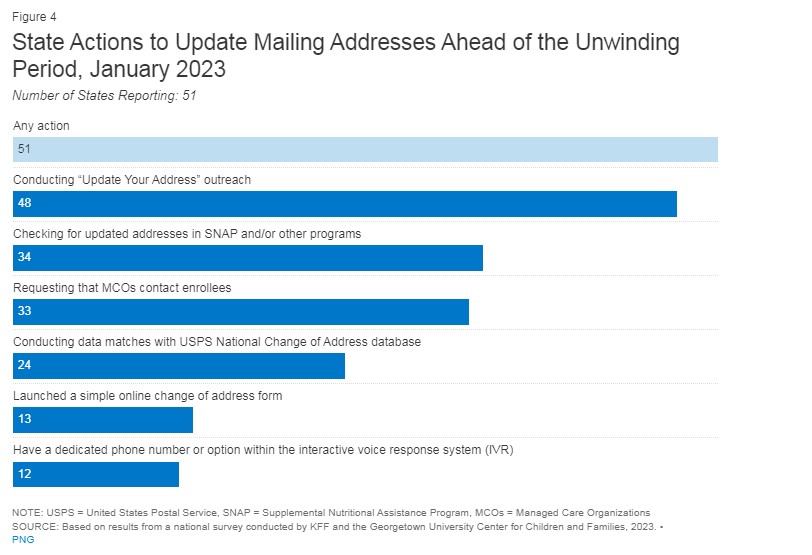

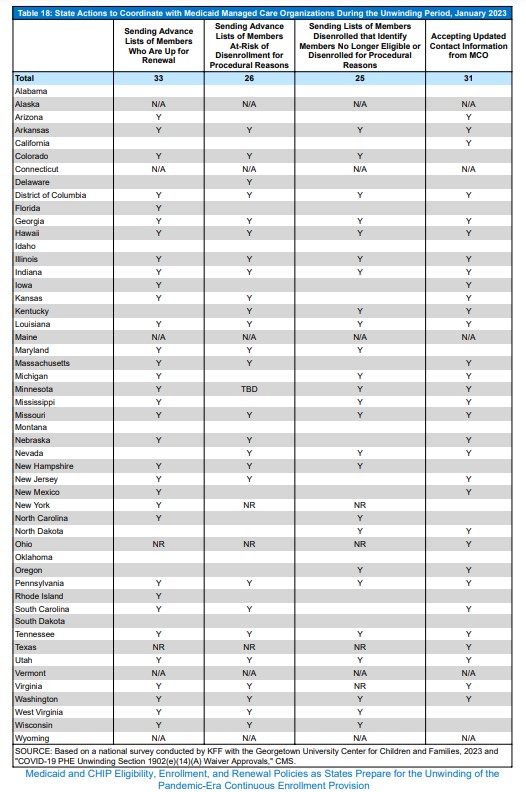

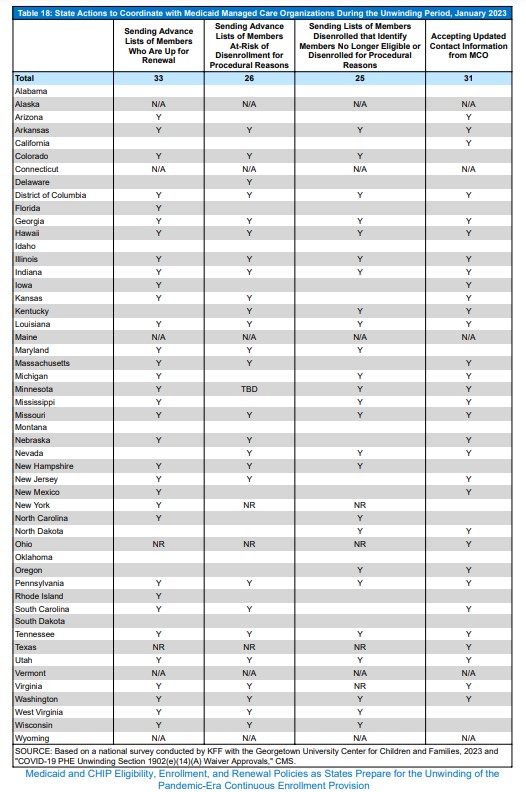

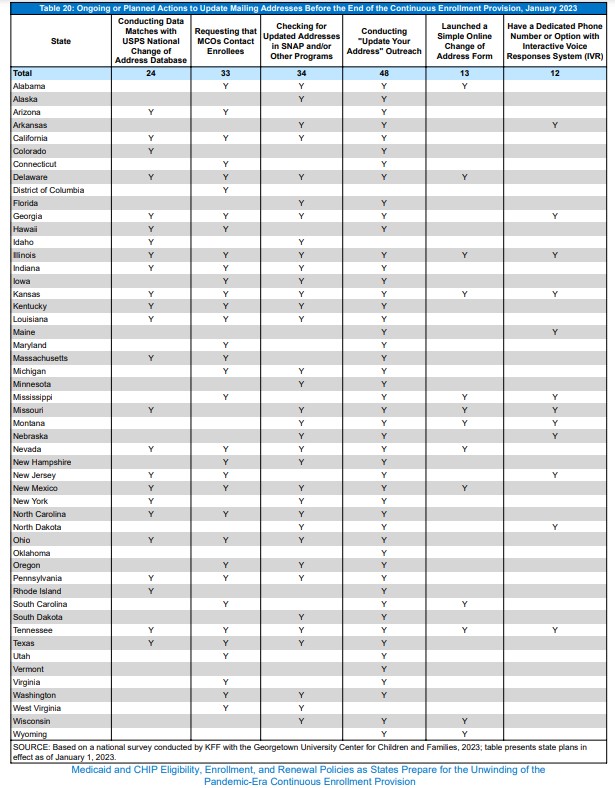

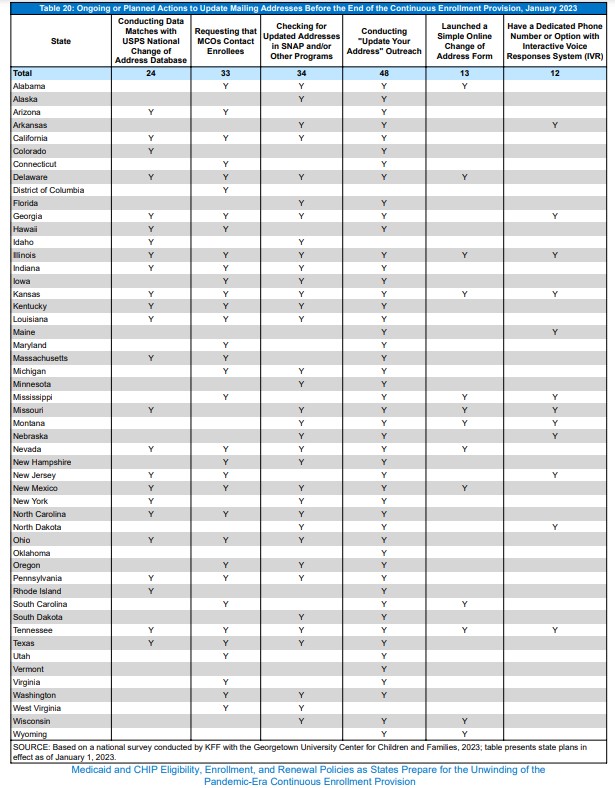

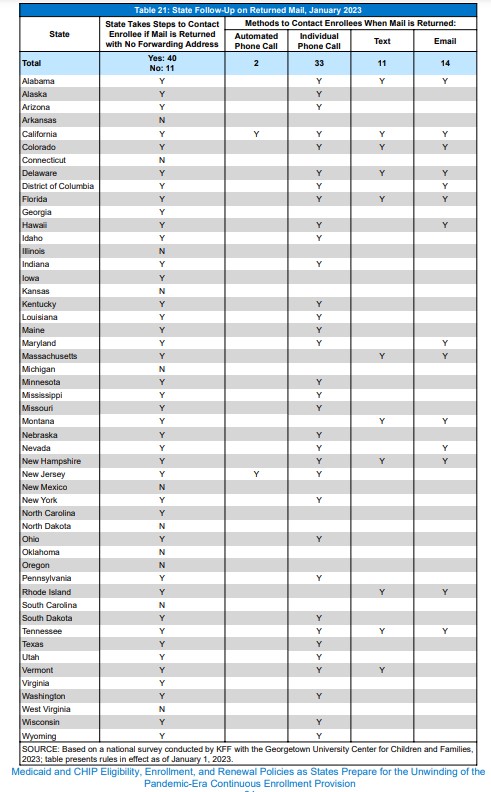

All states have taken action to encourage enrollees to update their contact information with most states taking a multi-pronged approach. Having updated enrollee contact information will increase the likelihood that enrollees receive important renewal and other notices during the unwinding period. State actions include conducting comprehensive outreach and communications campaigns, including using social media (48 states); checking data from other assistance programs (34 states); working with MCOs (33 states); and using the USPS National Change of Address database (NCOA) (24 states). Thirteen states have created simple online change of address forms and 12 states have a dedicated phone number or option within the interactive voice response system to report changes. States must continue to take steps to update contact information and make a good faith effort to contact an individual before terminating coverage for returned mail to qualify for the enhanced federal funding available until the end of 2023.

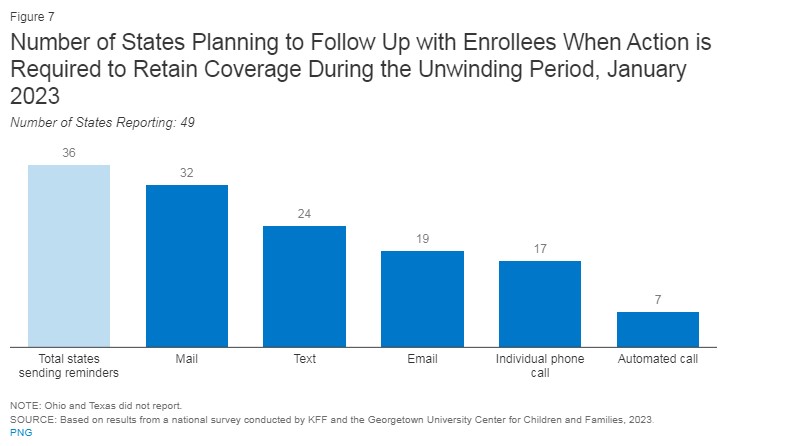

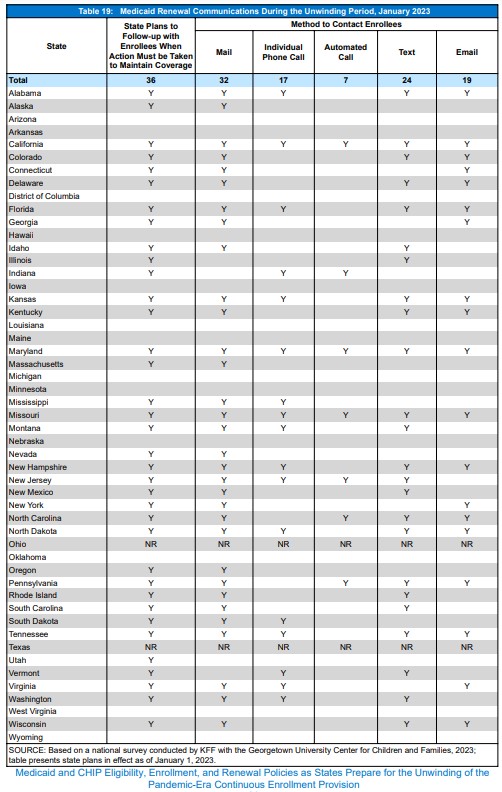

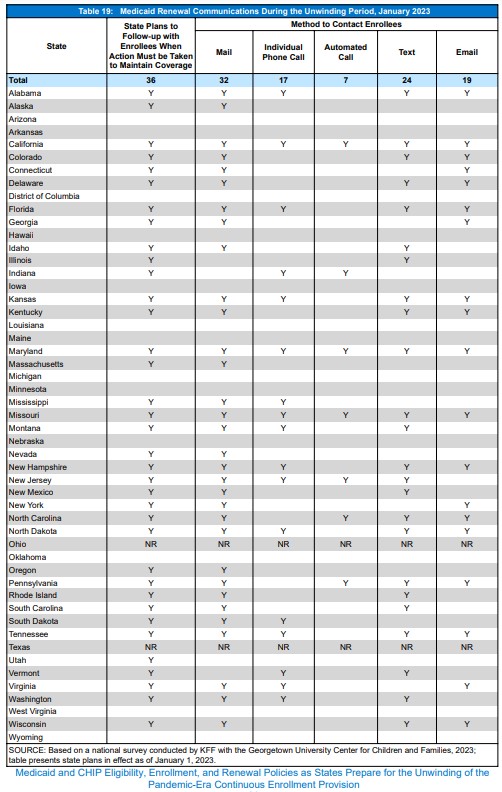

Over two thirds of states (36) plan to follow-up with enrollees when action is required to maintain coverage. Reminders to return renewal forms and submit requested information will increase renewal response rates, reduce the number of procedural (non-eligibility related) disenrollments, and increase the share of account transfers to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace for individuals who are no longer eligible. Most states (32) plan to follow-up by mail; 19 states will use individual phone calls, automated phone calls, or both; 24 states will follow-up through text messages and 19 states plan to use email.

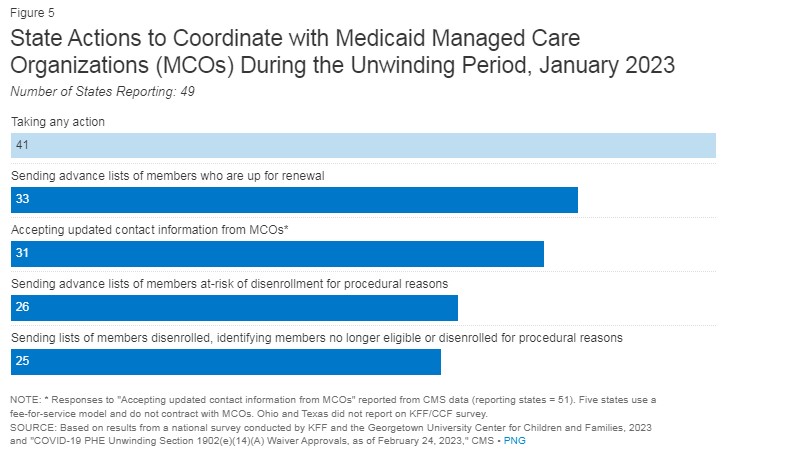

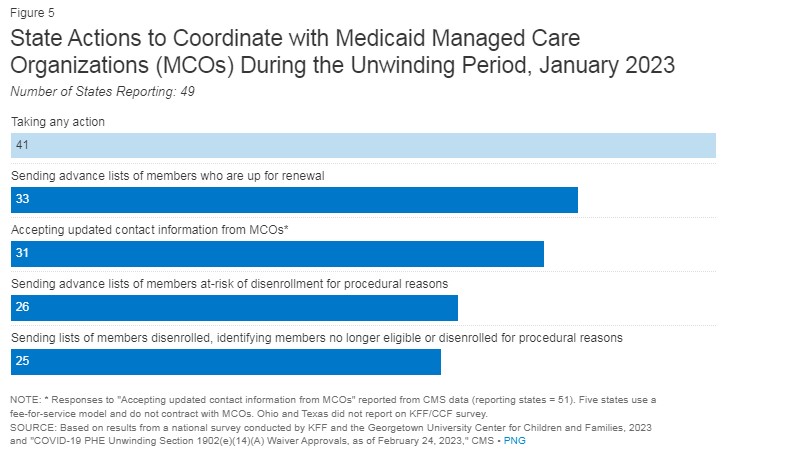

A majority of states (41) are engaging managed care organizations (MCOs) to conduct outreach and assist members. With a majority of Medicaid enrollees in managed care, MCOs have an interest in retaining members and have resources to supplement the state’s capacity to update contact information, amplify state communications, and assist enrollees with renewals or transitions to other coverage. States are providing MCOs with advance lists of members up for renewal (33 states); advance lists of members who may be disenrolled because they have not responded to requests for information (26 states); and lists of members who have been disenrolled noting whether they were determined ineligible or disenrolled for procedural reasons (25 states). Also, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has approved temporary waivers for 31 states to accept updated contact information verified by the MCOs without repeat verification by the state.

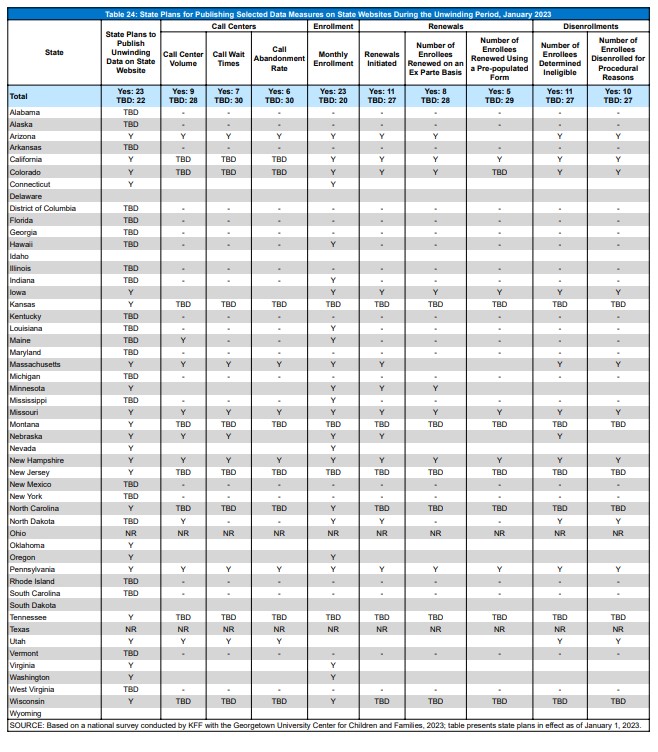

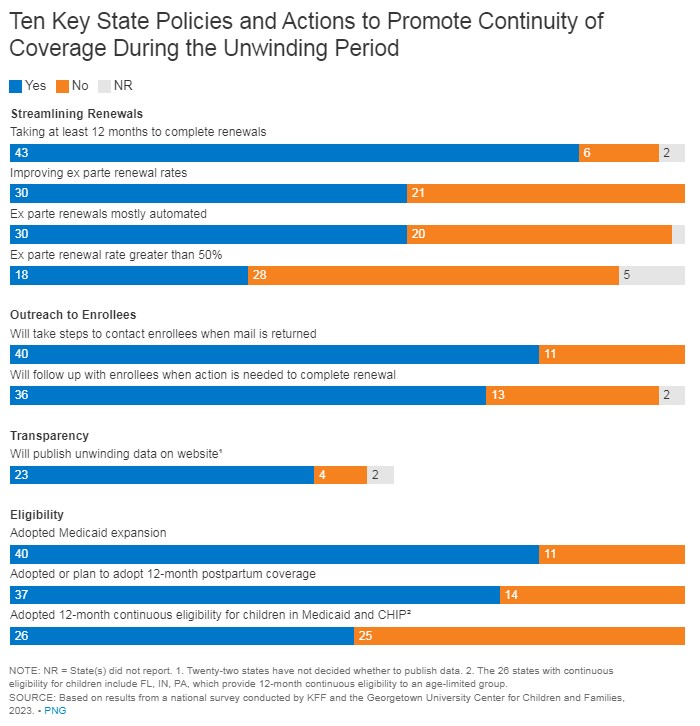

Most states collect the required unwinding monitoring data but less than half of the states (23) have committed to posting the data on their websites. An additional 22 states indicate a decision to post data has not yet been made. The data will aid in promoting transparency and accountability during the unwinding process. The CAA requires states to report specific unwinding data, as well as other data required by CMS, and failure to do so could result in financial penalties. While CMS is required to post state-level data, the timeliness of nationally reported data may be insufficient for rapid response. Posting more quickly at the state level could identify early problems, particularly if enrollees are losing coverage inappropriately.

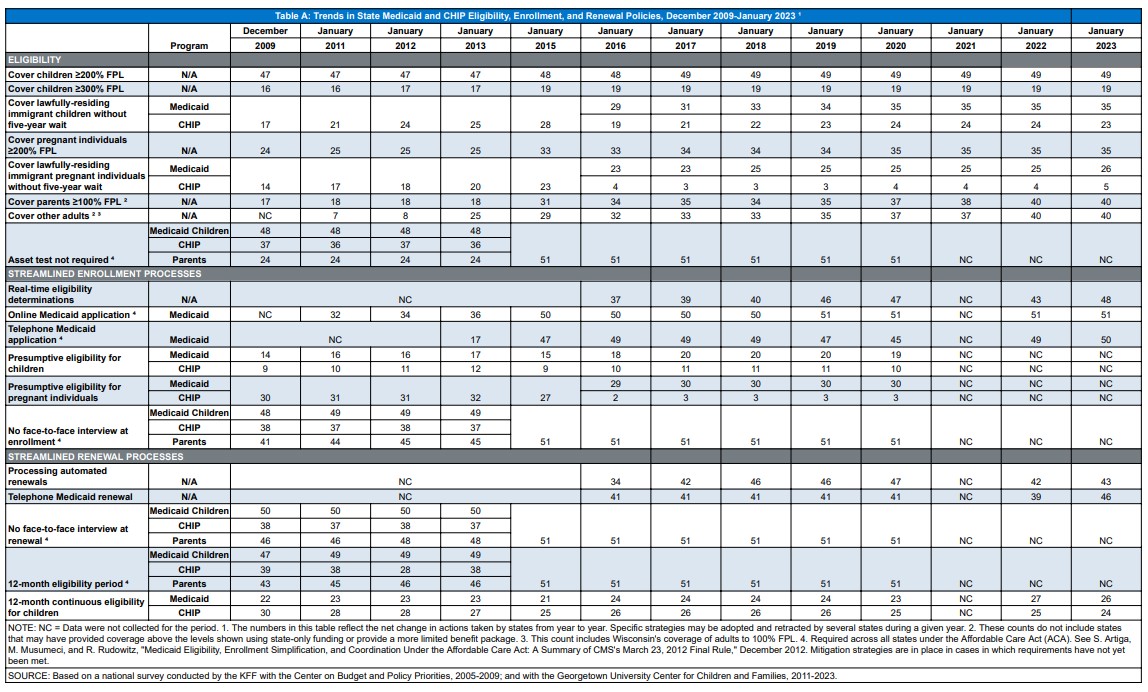

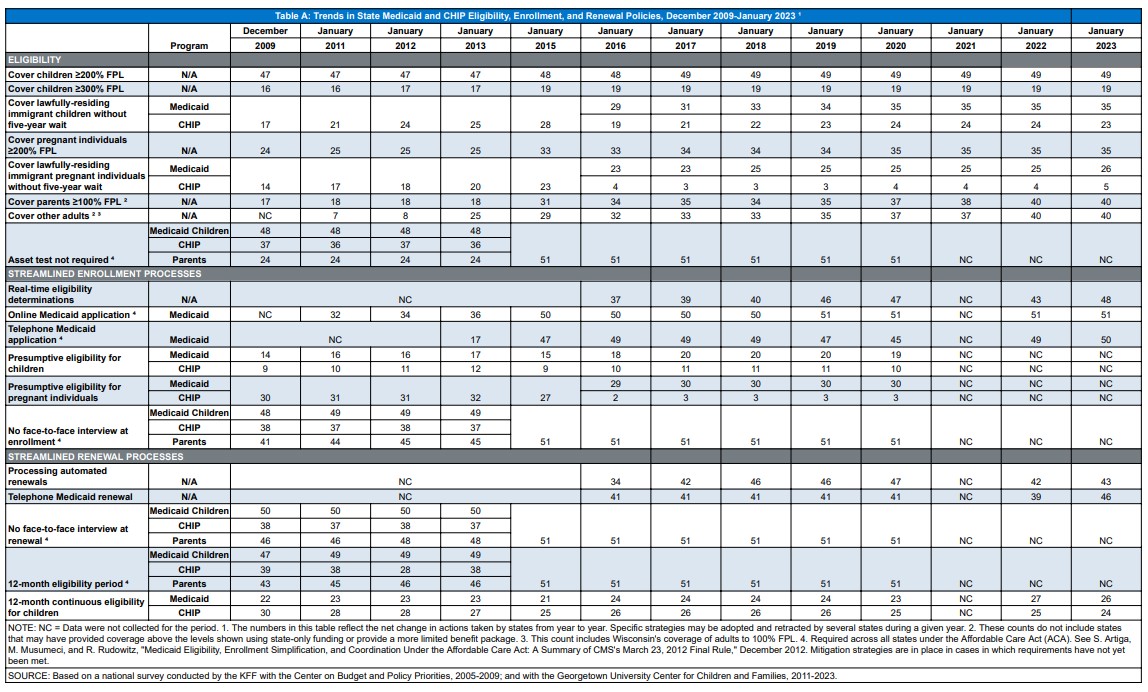

Systems and Enrollment Policies

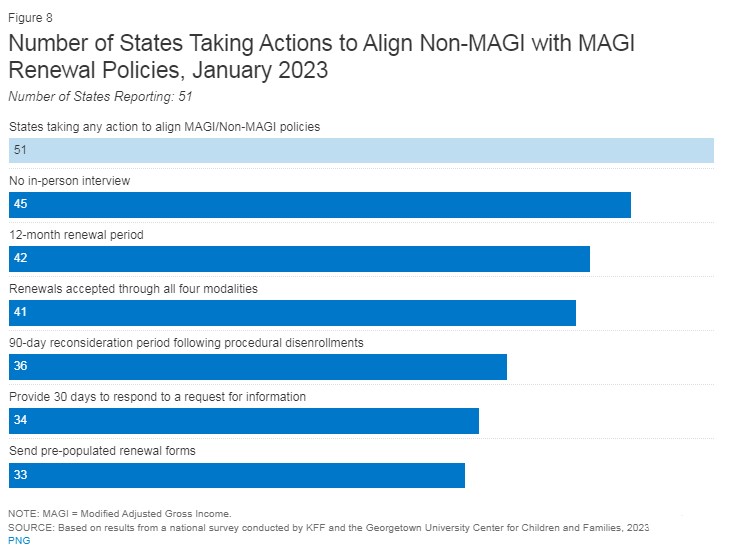

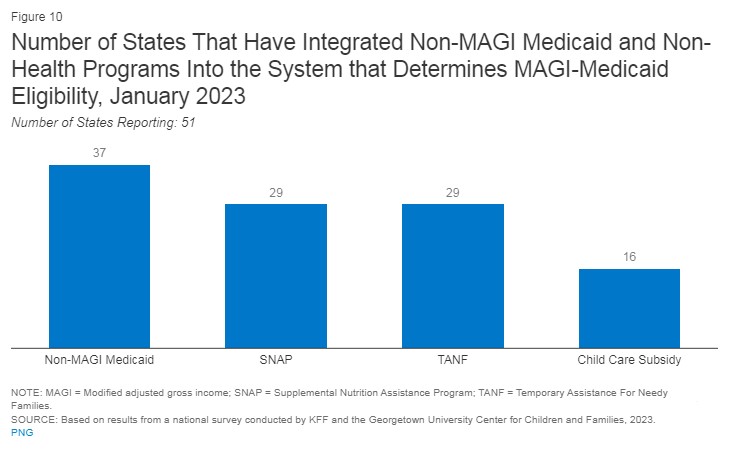

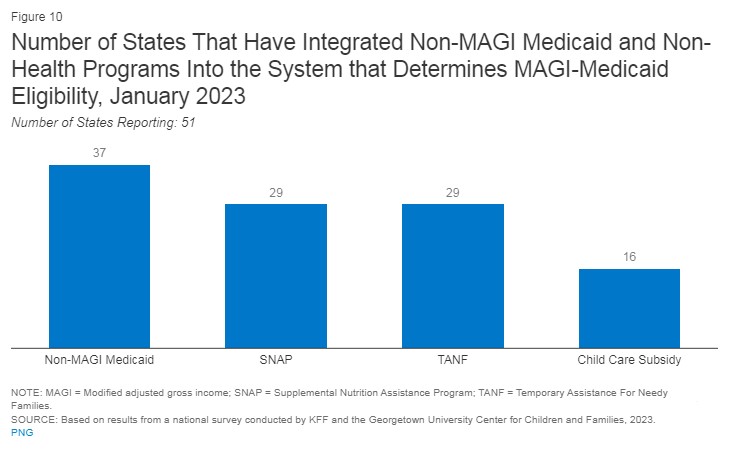

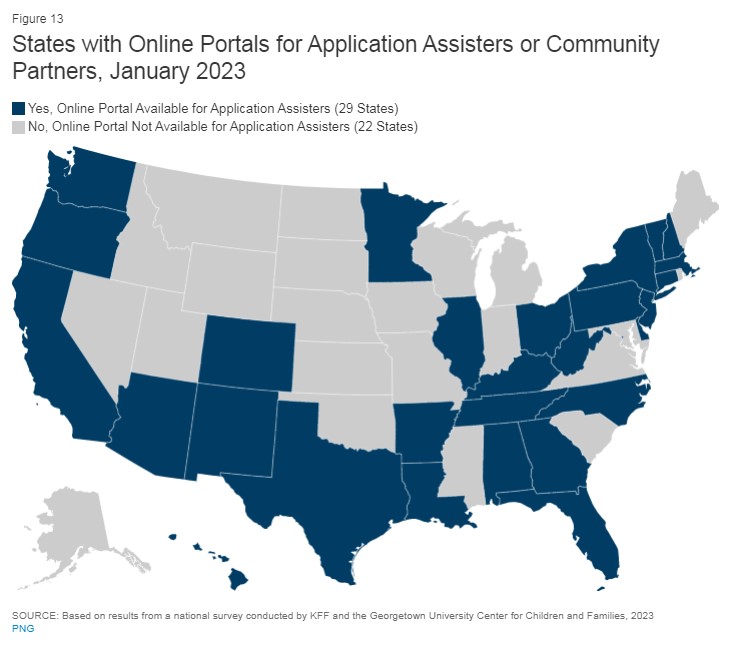

States continued to make incremental improvements to systems and enrollment policies as they prepare for the unwinding. Nearly all states allow enrollees to create online accounts and states have added features to their online accounts, including allowing enrollees to renew their coverage through their online account. Two-thirds of states (37) have integrated non-MAGI into the Medicaid systems, and over half of states use the Medicaid system for SNAP and TANF. All states have taken some steps to align renewal policies for non-MAGI and MAGI groups. Over half of the states (29) now have online portals that allow community partners and assisters to submit applications and assist applicants and enrollees with enrollment and renewal.

Eligibility Policies

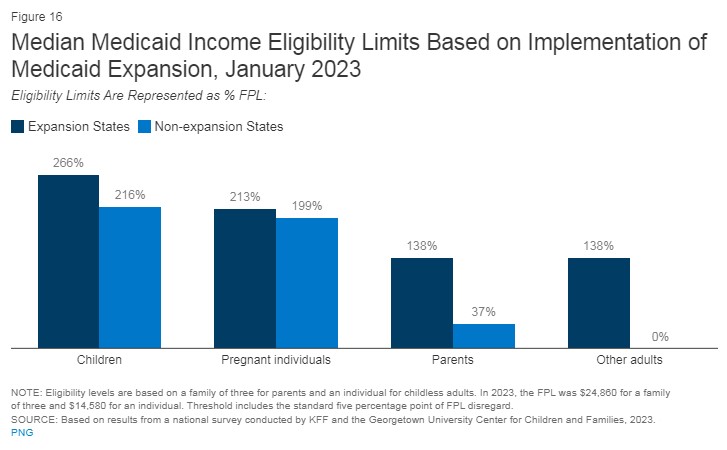

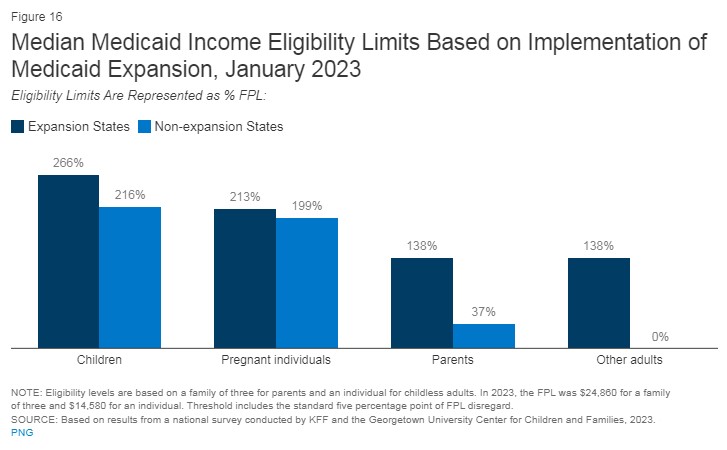

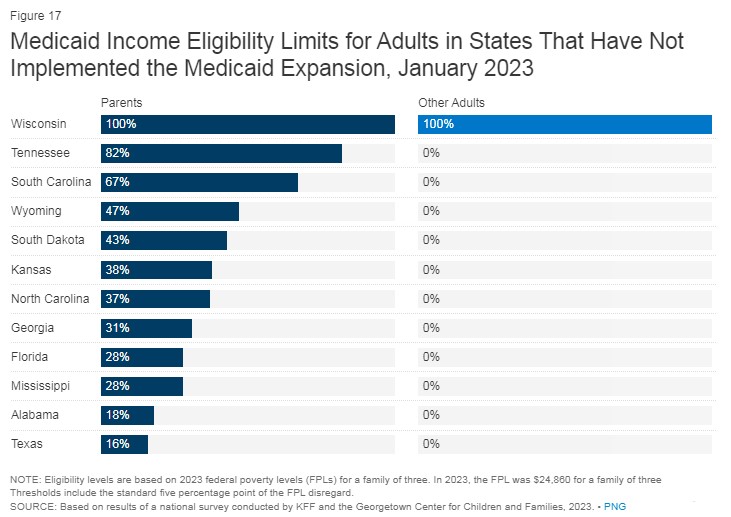

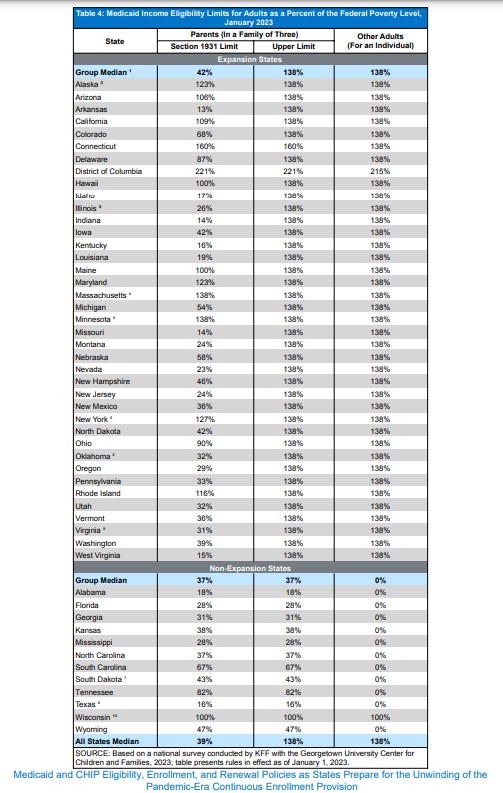

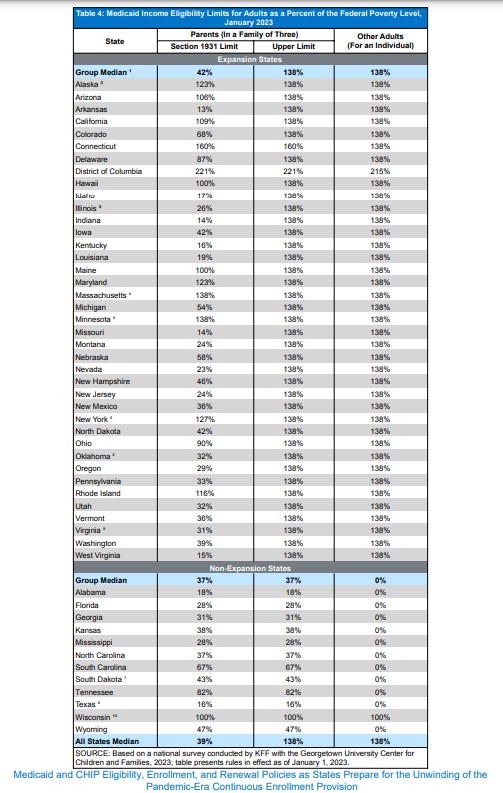

South Dakota became the seventh state to approve a ballot initiative to adopt the Medicaid expansion, which will be implemented in July 2023. Legislators in North Carolina announced an agreement to move ahead with expansion that will be voted on later this year. Many low-income parents in the remaining non-expansion states who lose coverage during the pandemic will find themselves in the coverage gap without options to obtain affordable coverage. Most non-expansion states base eligibility for parents and caretakers on a dollar threshold, which is not routinely adjusted. As a result, the median eligibility for parents in non-expansion states, converted to an FPL equivalent level, declined from 39% FPL in 2022 to 37% FPL in 2023. In Medicaid expansion states, eligibility is extended up to 138% FPL for all adults, irrespective of family status.

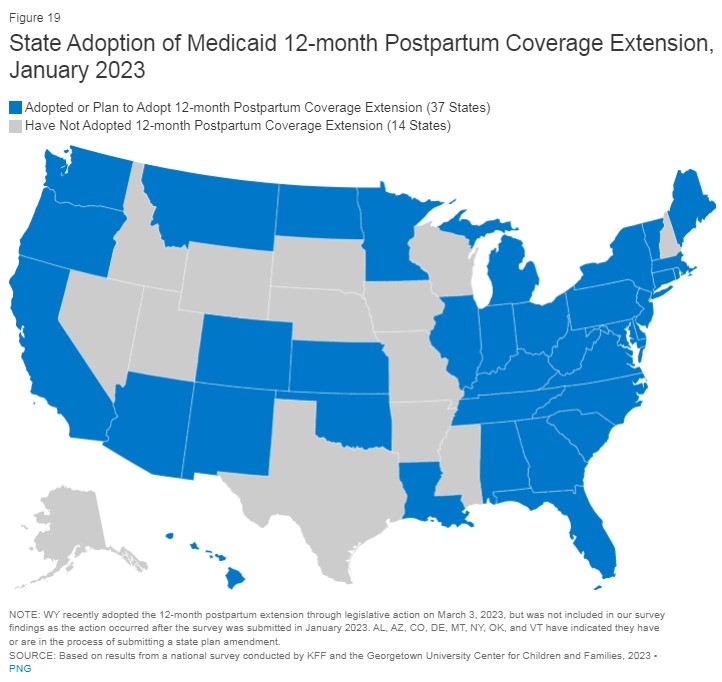

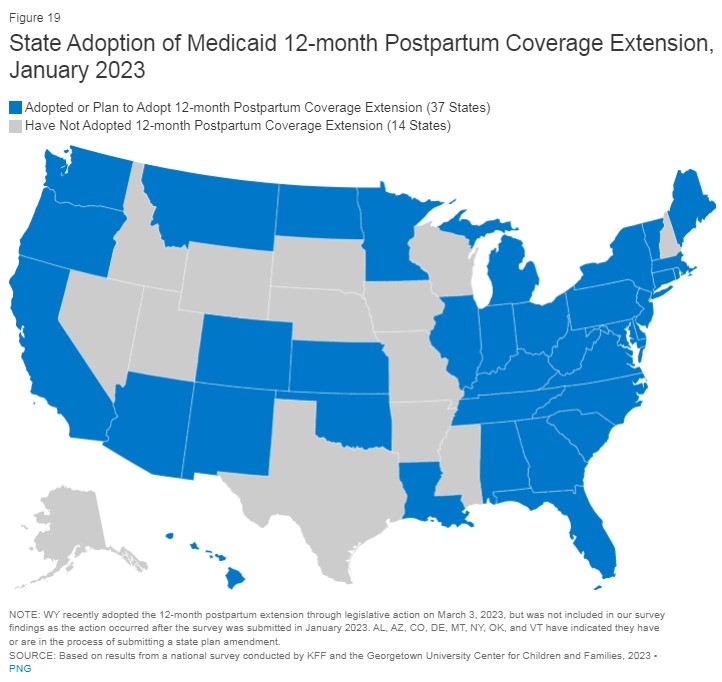

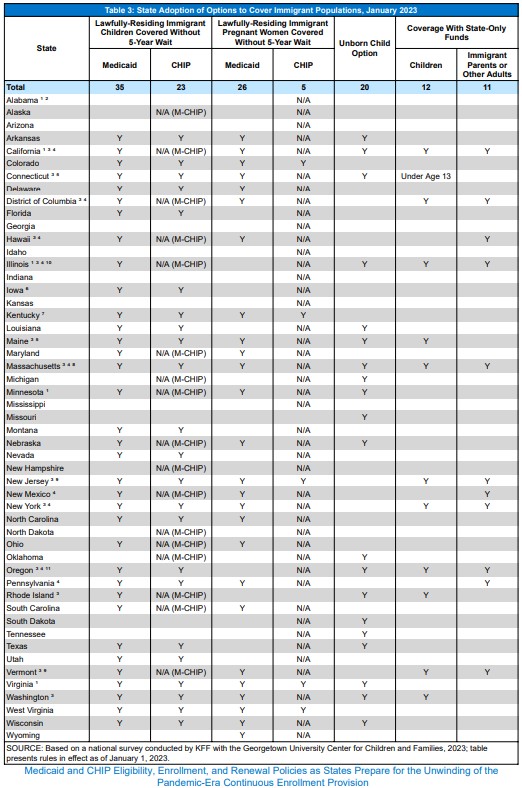

States have taken action to improve maternal and immigrant coverage in Medicaid during the pandemic. More than two-thirds of states (37) have now extended or plan to extend postpartum coverage for a full 12-months post pregnancy. Kentucky and Oklahoma increased income eligibility levels for pregnancy coverage. Kentucky also removed the five-year bar for pregnancy coverage of lawfully-residing immigrants in Medicaid and CHIP. Connecticut and Maine adopted the CHIP unborn child option, effectively providing pregnancy coverage regardless of immigration status. Connecticut, Maine, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Vermont are now using state funds to cover children regardless of immigration status while Illinois, Oregon and Vermont are also using state funds to newly cover some adults who are not eligible for Medicaid due to immigration status.

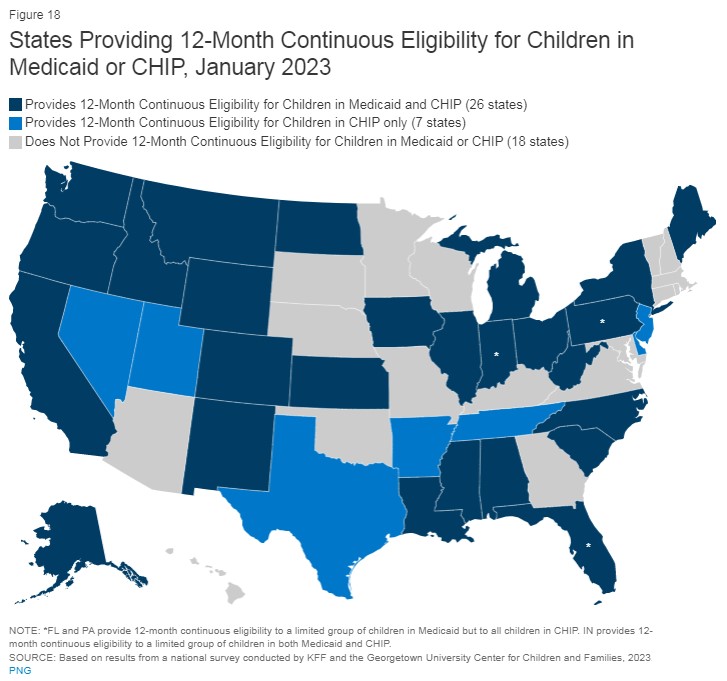

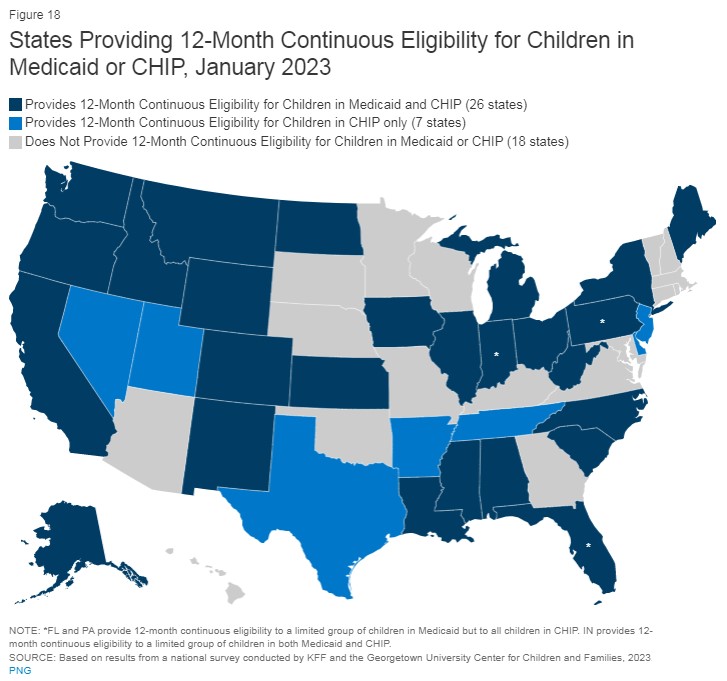

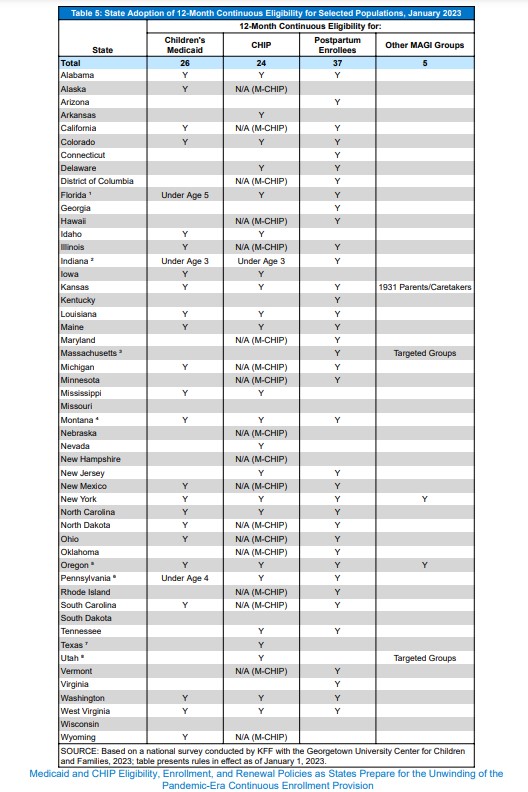

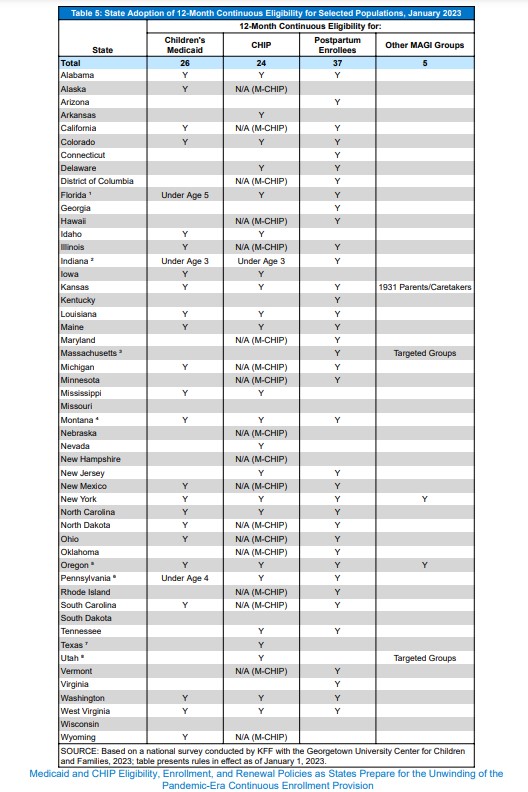

Nearly two-thirds (33) of states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid and/or CHIP, while several states are moving toward multi-year continuous eligibility. Of these 33 states, 26 provide continuous eligibility in both Medicaid and CHIP to some or all children while seven states provide it in CHIP only. All states will be required to adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for children by January 2024. Additionally, several states are working to cover children for longer periods. Oregon became the first state to receive approval to cover children continuously until their sixth birthday; three other states, California, New Mexico, and Washington, have similar plans. Oregon also received approval to provide two-year continuous coverage for all other ages, a policy that Illinois is planning to adopt.

Looking Ahead

States are moving from planning for the end of the continuous enrollment provision to implementation of their unwinding plans, but the impact of the unwinding will vary by state. How the unwinding impacts Medicaid enrollees and state budgets will vary significantly from state to state depending on each state’s systems capabilities, including ex parte renewal rates; communications strategies; staff capacity; and adoption of operational policies that make it easier for people to stay enrolled.

It is likely that the uninsured rate will increase as states resume Medicaid disenrollments. Most people who are disenrolled from Medicaid because they are no longer eligible should have a path to other coverage options through the Marketplaces or an employer, but knowledge of how and where to apply as well as affordability concerns may remain a barrier for some. Research indicates that 65% of people disenrolled from Medicaid experience a period of uninsurance in the year following disenrollment. At the same time, disenrollments for procedural reasons among people who remain eligible are expected to be high. Boosting staff resources and consumer assistance capacity, actively monitoring the unwinding to identify issues, and rapidly responding to systemic or recurring problems can help avoid disenrollments that lead to coverage losses.

CMS is working to finalize rule changes to streamline eligibility and enrollment, promote access and improve quality, while at the same time, Congress may debate eligibility restrictions and cuts to Medicaid and other assistance programs. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Regulatory agenda calls for finalizing changes relating to eligibility and enrollment, access and managed care, mandatory reporting of the child core set of healthcare quality measures, and anti-discrimination. In connection with the need to raise the government’s debt ceiling, interest in putting restrictions on Medicaid enrollment, such as work requirements, have resurfaced in Congress, along with strategies to slow the growth in Medicaid spending that largely shift increasing costs on the states by putting constraints on federal funding through per capital caps or block grants. How serious this debate is remains to be seen.

Introduction

Throughout 2022, the coronavirus public health emergency continued to have significant impacts on states. Since its emergence in early 2020, the coronavirus’ dual economic and public health crises continued to expose significant disparities in the public health infrastructure and further highlighted the importance of health coverage. Provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES), required states to maintain eligibility and enrollment standards and provide continuous enrollment in Medicaid until the end of the public health emergency (PHE) to qualify for a 6.2 percentage point increase in Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). During this time, states also adopted temporary changes in their state Medicaid plans through disaster-related authorities and temporary waivers to streamline processes and connect individuals to coverage more quickly, such as by expanding the use of presumptive eligibility, waiving premiums and cost-sharing, and allowing self-attestation of certain eligibility criteria. Largely due to the continuous enrollment provision, KFF estimates that Medicaid and CHIP enrollment will have grown by 23.3 million or over 30% by the time the continuous enrollment provision ends.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), enacted in December 2022 delinked the continuous enrollment provision from the PHE, ending continuous enrollment on March 31, 2023. The CAA also phases down the enhanced FMAP through December 2023; states must meet certain maintenance of eligibility, data reporting, and other requirements to continue to qualify for the enhanced funding. CMS quickly released additional guidance on January 5, 2023 and January 31, 2023 on changes enacted by the CAA), in addition to providing technical assistance to states throughout 2022.

In this context and just after the CAA passed, KFF and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families (CCF) fielded the 21st annual survey of Medicaid and CHIP program officials in the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) in January 2023. In anticipation of the end of the continuous enrollment provision, this year’s survey focuses on actions states are taking to prepare. It also provides data on state Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels and presents a snapshot of key aspects of state enrollment and renewal procedures in place as of January 2023. The report focuses on policies for children, pregnant individuals, parents, and other non-elderly adults whose eligibility is based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) financial eligibility rules; it reports only limited policies for groups eligible through Medicaid pathways for adults over the age of 65 or on the basis of disability. All states responded to the survey although response rates for specific questions varied. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for purposes of this report.

Preparing for the End of the Continuous Enrollment Provision

Unwinding Planning

Passage of the CAA in late 2022 started the countdown to the end of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision as of March 31, 2023, prompting states to finalize their unwinding plans and shift toward implementation of those plans in the first quarter of 2023. States were expected to submit a State Renewal Report to CMS by February 15, outlining how they plan to distribute renewals over the unwinding period and describing the processes and strategies the state is considering or has adopted to avoid inappropriate coverage loss during the unwinding period. There is no requirement for states or CMS to publicly post these reports, but this survey reflects state responses to questions that are similar to information contained in the State Renewal Reports.

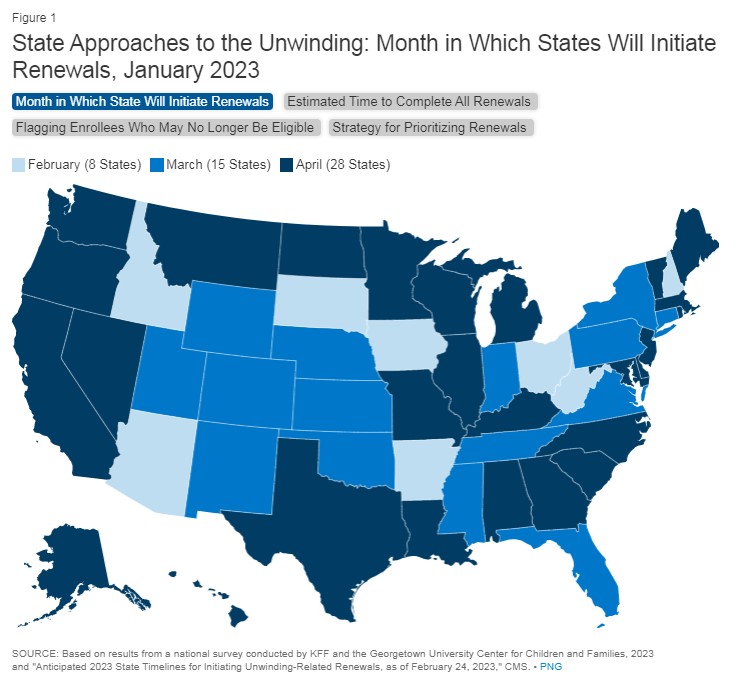

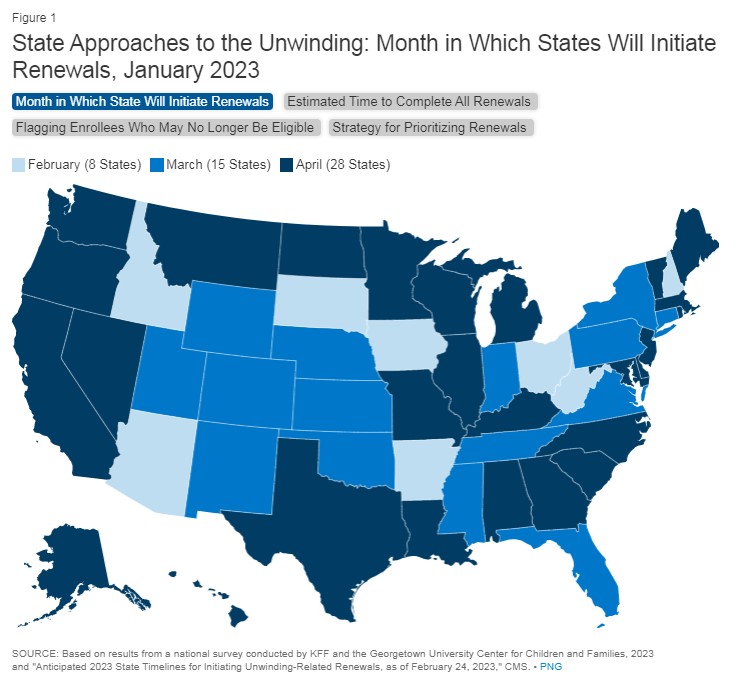

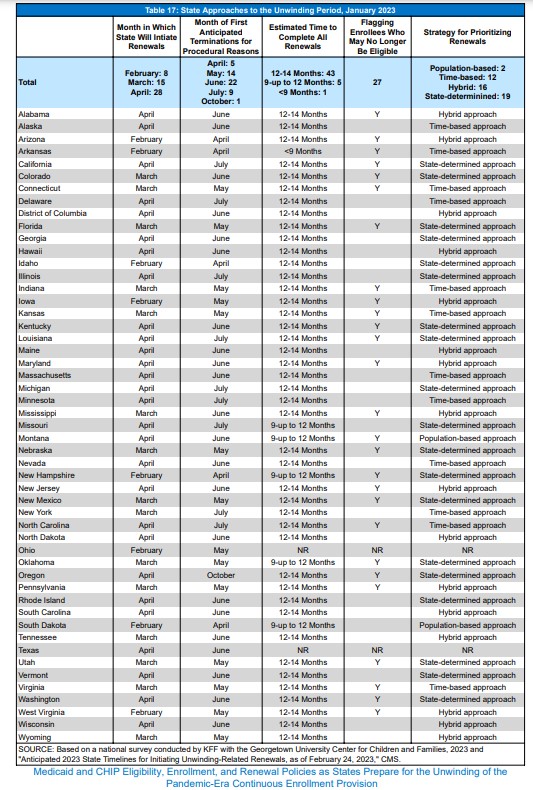

Over half of states are waiting until April to initiate their “unwinding” plans and most plan to spread renewals over 12 to 14 months. States may start the unwinding process (initiate the first batch of renewals) in February, March or April, but more than half of the states (28) are waiting until April to being the unwinding process, with 15 states starting in March and eight states in February (Figure 1). A majority of states (43) plan to take the full 12 to 14 months to complete the process and return to routine operations; five states plan to take 9 to 12 months, only one state plans to wrap up the process in less than 9 months, and two states did not report how long they plan to take. Spreading the work over a longer period will help states balance the unprecedented volume of work ahead with limited staff capacity, and more evenly distribute future renewals, but will also increase state spending as Medicaid enrollment remains higher for a longer period of time.

Most states (35) are adopting an approach to prioritizing renewals that considers multiple factors, including time since last renewal and potential ineligibility. States are required to develop a plan for how they will prioritize renewals, taking into consideration the need to prevent inappropriate terminations and promote smooth transitions to other sources of coverage for people determined ineligible. Only two states are adopting a population-based approach that prioritizes cohorts of enrollees likely to be eligible for more expansive benefits or other coverage. Another 12 states are adopting a time-based approach using existing renewal dates, taking steps to distribute renewals evenly across the unwinding period, or processing renewals based on the length of time the renewal or change has been pending. But most states want more flexibility to mix and match approaches—16 states are taking a hybrid approach (a combination of population- and time-based approaches) and 19 states are using a state-determined approach (Figure 1). Several states will focus first on enrollees who have been flagged as potentially ineligible, followed by enrollees without a renewal in the past year. Some states are aligning Medicaid renewals with other programs, most often the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP). Several states have also indicated they will take the health care needs of enrollees into account, prioritizing enrollees who are not utilizing health care services and deprioritizing individuals with more extensive health care needs.

About half of the states (27) have been flagging individuals who may no longer be eligible or who did not respond to renewal requests, including six states that are conducting data matches to identify these individuals (Figure 1). States that have continued processing renewals have been able to flag individuals who they have confirmed are no longer eligible or appear to no longer be eligible, although not all states have done so. However, only a small number of states indicated that they plan to prioritize renewals for “flagged” enrollees early in the process.

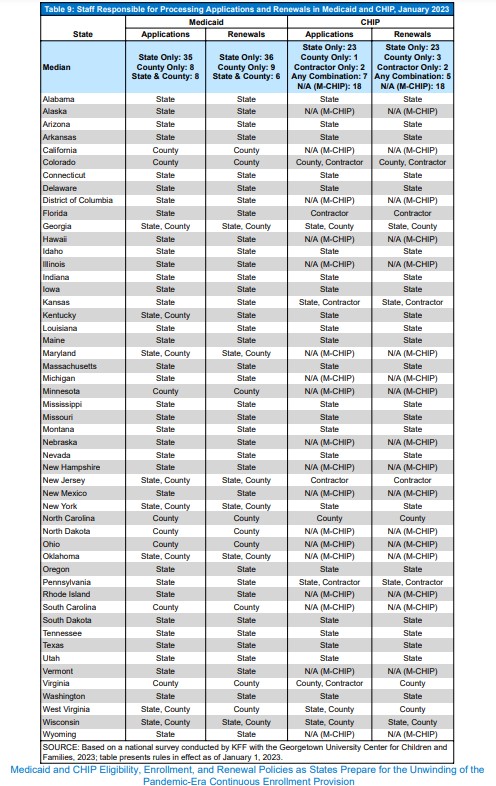

Staff Capacity

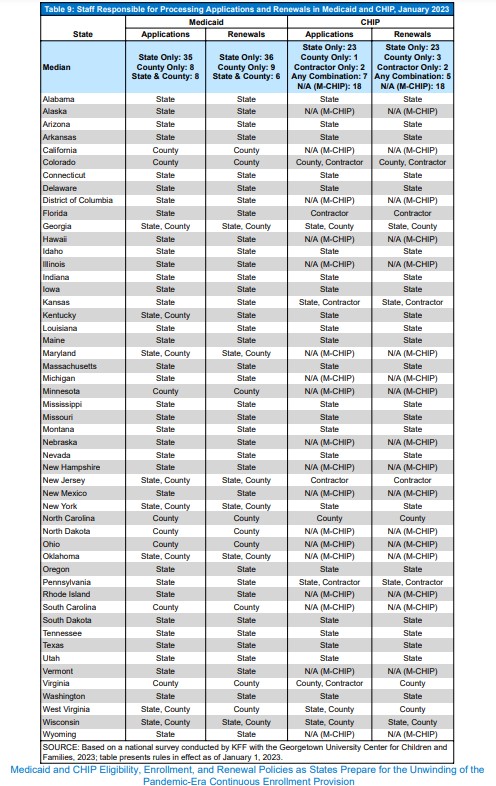

In over two-thirds of the states, the state is solely responsible for Medicaid eligibility determinations while a handful of states rely on counties to administer eligibility or share responsibility with the counties. Thirty-five states take full responsibility for processing Medicaid applications and 36 states process all Medicaid renewals. Eligibility determinations at application are delegated to the counties in 8 states and for renewals in 9 states. States and counties share responsibility for applications in 8 states and renewals in 6 states. In states that rely solely or partially on counties, Medicaid applicants and enrollees may have different experiences depending on where they live. Separate CHIP programs have more flexibility in using contractors to assist with eligibility determinations. In 23 of the 33 states with separate CHIP programs, the state is solely responsible for processing CHIP applications and renewals. Counties determine CHIP eligibility in one state for applications and three states for renewals. Two states use contactors for CHIP applications and renewals, and a few states use a combination of state, county, and contractor staff to determine eligibility for applications and renewals.

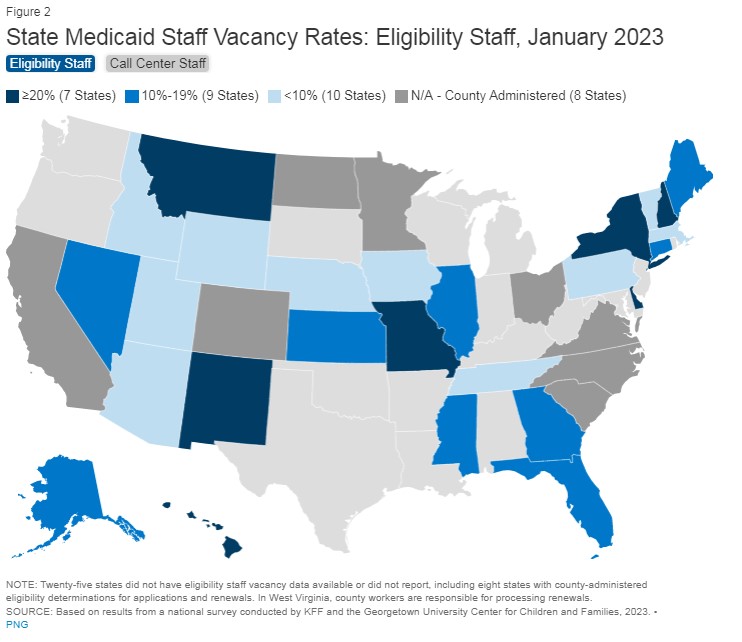

States face challenges in hiring critical eligibility and call center staff needed to process the unprecedented workload ahead. In 16 of 26 reporting states, eligibility worker vacancy rates exceed 10%, including seven states where more than 20% of eligibility positions are unfilled (Figure 2). In 13 of 28 reporting states, call center staff vacancy rates also exceed 10%, including five states where more than 20% of positions are unfilled. Some states report that call center contractors are responsible for staffing decisions. Several states also noted high turnover rates and time needed to train new workers as additional challenges.

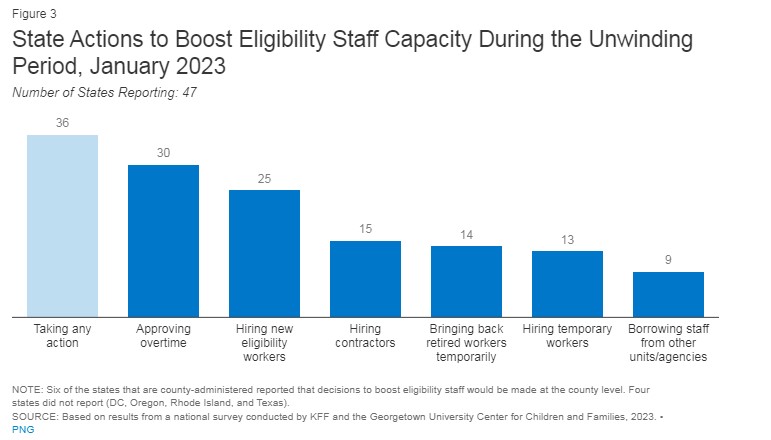

States are adopting multiple strategies to address eligibility staffing shortages, although it is less clear how counties that process eligibility are gearing up for the unwinding. State strategies include approving overtime (30 states) and hiring new staff (25 states), temporary workers (13 states), or contractors (15 states), and bringing back retirees (14 states, Figure 3). It is less clear what actions are being taken to boost capacity in the states that rely solely or partially on counties to conduct renewals, although several states noted that they are providing additional resources to counties to mitigate staff shortages.

Updating Contact Information and Returned Mail

All states have taken steps to update enrollee contact information; two-thirds of states are using multiple strategies. Outdated contact information and returned mail have been longstanding problems in Medicaid and the impact of housing displacements during the three-year COVID-19 public health emergency has exacerbated difficulties in reaching enrollees by mail, the primary method states use to send renewals and requests for information. Ten states use a service or system, such as the USPS National Change of Address database (NCOA), to routinely update addresses for enrollees, but in anticipation of the unwinding states have been using a variety of tactics to update enrollee contact information. These include conducting data matches with the USPS NCOA (24 states); working with MCOs (33 states); checking for updated addresses in SNAP or other benefit programs (34 states); conducting “update your address” outreach campaigns (48 states); launching a simple online change of address form (13 states); and providing a dedicated a phone number or option within the interactive voice system for reporting updated information (12 states, Figure 4). To comply with the new CAA requirement, states must use recent and reliable information, or have recently attempted to obtain up-to-date contact information, before initiating a renewal.

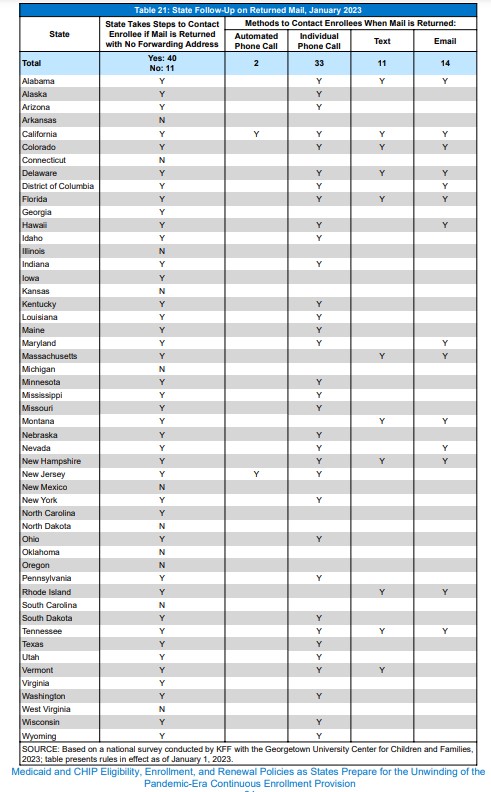

Most states (40) attempt to contact enrollees when mail is returned; during the unwinding, all states are required to make a good faith attempt to contact an enrollee through at least two modalities prior to disenrolling when mail is returned. CMS has previously provided guidance to the states on dealing with returned mail, depending on whether mail is returned with an in-state, out-of-state, or no forwarding address. Of the 40 states taking action on returned mail through non-mail means, most states (33) follow up by telephone, 14 states use email, and 11 states use text to contact enrollees about the need to update their mailing address. The CAA requires states to make a good faith attempt to contact any enrollee through at least two modalities during the unwinding before disenrolling them based on returned mail. CMS guidance defines good faith attempt as 1) the state has a process in place to update mailing addresses and alternate contact information and 2) the state attempts to reach an individual whose mail is returned through at least two modalities using the state’s updated contact information, unless the state is unable to obtain any alternate contact information. States must also document their returned mail policies in their unwinding operational plan.

Other Unwinding Actions

Most states (41) are engaging MCOs in conducting outreach and assisting members with renewals. A majority of Medicaid enrollees are covered through managed care arrangements, and MCOs have an interest in keeping eligible members enrolled. CMS has clarified how states may engage with MCOs, including providing states with temporary waiver authority to accept updated contact information from MCOs without re-verifying the information with enrollees; 31 states have received such approval (Figure 5). States are engaging MCOs in other ways, including by providing advance lists of members up for renewal (33 states), advance lists of members at risk for disenrollment because they have not responded to a renewal request (26 states), and lists of members who have been disenrolled noting if the member was determined ineligible or was disenrolled for procedural reasons (25 states).

Most states with state-based ACA marketplaces (SBM) are planning a variety of outreach, communications, and marketing strategies to smooth transitions from Medicaid to the Marketplace, but challenges remain in states without integrated Medicaid and Marketplace systems. Of the 18 SBM states with their own Marketplace systems, 16 states are planning specific outreach strategies aimed at ensuring a smooth transition between Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. Actions largely focus on deploying a variety of outreach, communications, and marketing strategies and using local partners to conduct outreach. In the eight SBM states that operate their own Marketplace system that is not integrated with Medicaid, account transfers are used to transition an individual from Medicaid to the Marketplace, much like the process in place for states that use the federal platform for eligibility and enrollment. In seven of those states (Colorado, DC, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania), Medicaid will send a notice with information and instructions on how to apply for Marketplace coverage. Also, in seven states (Colorado, District of Columbia, Idaho, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) the SBM will call or send a /notice to enrollees that their information has been received by the Marketplace. In six states (District of Columbia, Maine, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania), individuals may have to submit additional information or resubmit data already provided to Medicaid.

Monitoring the Unwinding and Estimating Coverage Impacts

States are required to report specific data needed to monitor the impact of the unwinding, and CMS is required to publish the state-level data. Having timely and reliable data from states on key metrics helps to monitor the unwinding process and assess if any state needs to take additional steps to avoid coverage losses among those who remain eligible. Unreasonable call wait times and high rates of disenrollments due to procedural reasons can signal early problems that could warrant oversight from CMS. The CAA requires states to report specific data relating to renewals, disenrollments, call center performance, and Marketplace transitions, as well as other data specified in the Unwinding Data Report and other Performance Indicator metrics required by CMS. While CMS is required to publish these monitoring data, there will likely be a lag in publishing the data, making it less useful when rapid response is needed. There is no requirement for states to report data publicly, and less than half of the states (23) indicate they will post some data on their websites, most often enrollment data, while 22 states indicated that they have yet to determine if they will post any data.

Among the just over one-third of states able to report, they estimate that about 18% of Medicaid enrollees will be disenrolled when the continuous enrollment provision ends. However, the estimates range widely across reporting states from about 7% to 33% of total enrollees. This estimated disenrollment rate is slightly higher than the 13% reported in 2022; however, it is consistent with other estimates indicating about 15 – 18 million people may lose Medicaid coverage over the coming year. Successfully transitioning individuals disenrolled who are no longer eligible into other coverage options, including CHIP and the Marketplace, could reduce the number who become uninsured.

Renewals

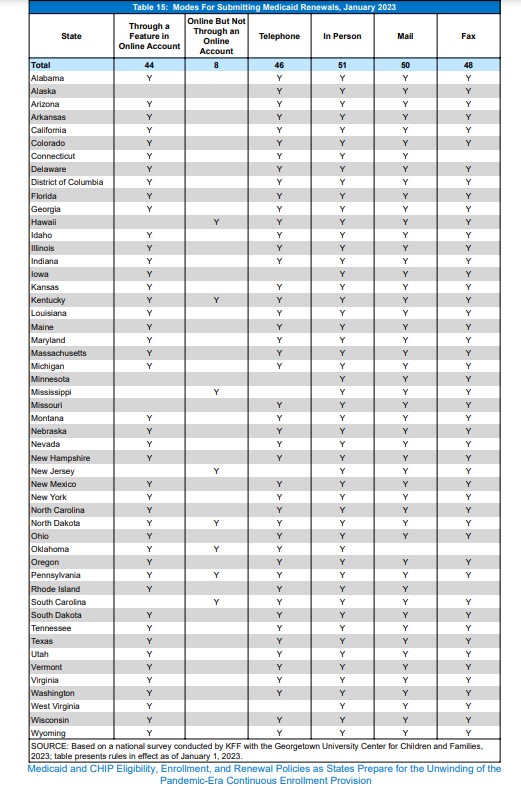

States must comply with all federal renewal requirements as a condition of receiving the enhanced federal funding enacted by the CAA through 2023. These requirements include accepting renewals through all four modes (online, phone, in-person, mail); using ex parte processes to automatically verify ongoing renewal before requiring the enrollee to submit forms or documents; sending pre-populated renewal forms (applies to MAGI groups); allowing a minimum of 30 days for a response; and re-processing eligibility if needed information is submitted within 90-day reconsideration period.

Most states (43) continue to process ex parte renewals. Federal regulations require states to attempt to automatically renew coverage for enrollees using reliable data available to the state, such as state wage or unemployment compensation data, before requiring an enrollee to complete a form or submit paper documentation. In the 43 states processing ex parte renewals, redeterminations are mostly conducted automatically by the system in 30 states. Four states report that most ex parte renewals require manual processing, and eight states indicate processing is a mix of manual and automated actions. Among states processing renewals, nearly two-thirds (32 states) are sending pre-populated renewal forms if they are unable to verify ongoing eligibility using electronic data sources. States with higher rates of renewals completed via ex parte will have fewer renewals to process manually, which eases the state’s administrative workload during a time when states face staffing challenges. Higher ex parte rates can also lower procedural disenrollments by removing barriers to renewal for enrollees, avoiding lost paperwork, and reducing manual processing errors. States that have also been sending prepopulated forms have been able to flag people who did not return renewal forms or respond to state requests for information, as well as those who were determined ineligible at the time of renewal.

Almost two-thirds of states (30) have taken steps to improve the share of renewals processed on an ex parte basis with 18 states reporting ex parte rates of over 50% as of January 2023, up from 11 states in January 2022 (Figure 6). During the pandemic CMS encouraged and assisted states in improving ex parte renewal rates, and 30 states have taken action to do so with most states (26) improving their system programming rules and seven states expanding the use of data sources. States also reported taking other steps including using temporary waiver authority to renew Medicaid based on SNAP or TANF data; automatically renewing enrollees with zero income; and increasing reasonable compatibility thresholds. Reasonable compatibility thresholds allow states to consider income as reasonably compatible if the difference between what an enrollee reports as income and what is found in data sources fall within a specific range.

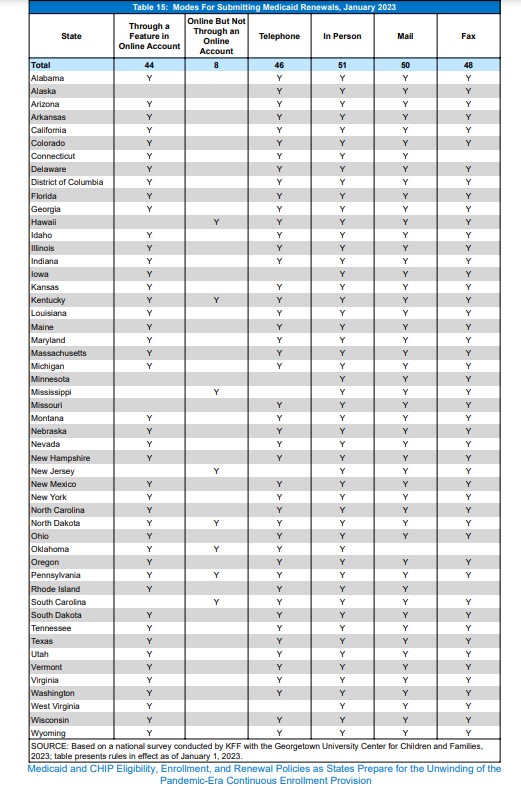

Most states (44) accept renewals through all four modes—online, in-person, by mail, and by phone. All states will assist enrollees with renewals in-person and 50 states accept paper renewals through the mail. In 48 states, individuals can renew online through their account, an online renewal form, or both, and 46 states process telephonic renewals using a telephone signature. CMS is working with states without all four modes on mitigation strategies that lead toward permanent compliance with all federal renewal regulations.

When the continuous enrollment provision is lifted, most states (36) plan to follow-up with enrollees when action must be taken to avoid a loss of coverage due to missing information. States must give MAGI-based enrollees 30 days to respond to a renewal request but there is no federal requirement for states to do more than send the renewal form, followed by a 10-day advance termination notice if the individual does not respond. However, sending reminder notices via mail, and through other communication modes, such as phone, text, and/or email, can increase the response rate to renewal requests. Follow-up reminders can also help reduce the number of people who remain eligible but are disenrolled at the end of the PHE because they did not respond to a request for information. Most of the states (32) plan to mail a reminder, 19 states will make individual or automated calls or both, 24 states will text reminders and 19 states will send email reminders (Figure 7). Overall, 30 states are planning to use multiple methods to follow up with enrollees.

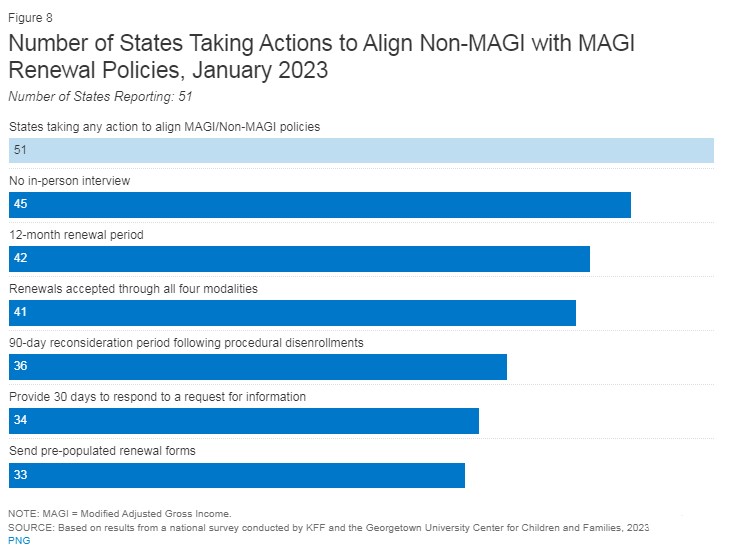

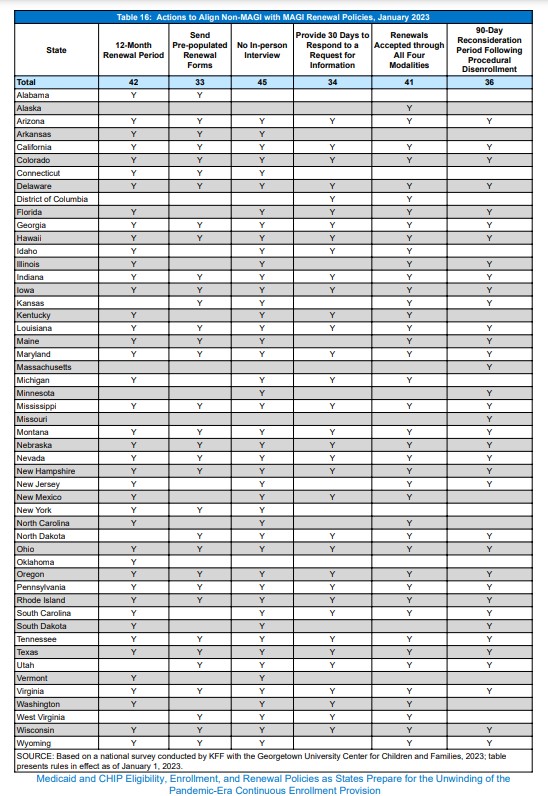

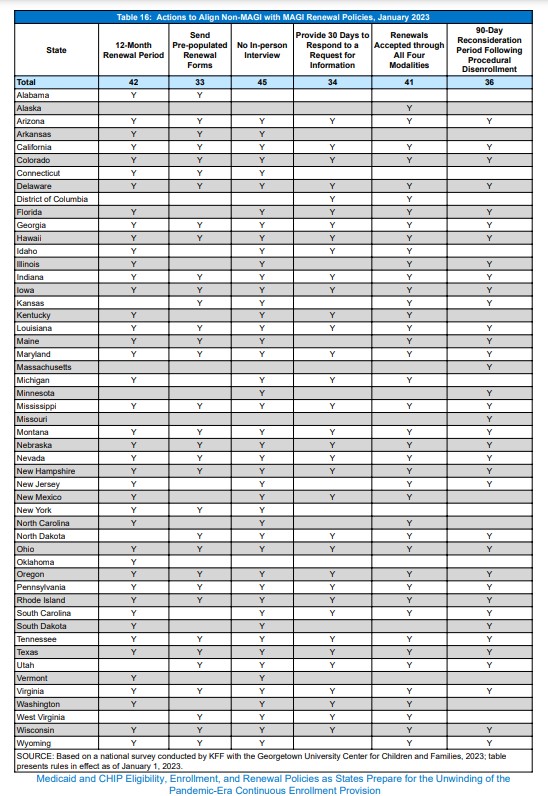

All states have taken at least one action to align renewal polices for non-MAGI groups with MAGI rules. Many of the renewal requirements enacted by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) applied only to coverage for children, pregnancy, parents, and expansion adults who are eligible under MAGI rules. In mid-2022, CMS proposed new eligibility and enrollment rules that will require states to align renewal policies, although most states have already taken steps to do so. State actions include eliminating in-person interviews (45 states); conducting annual renewals (42 states); sending pre-populated renewal forms (33 states); providing at least 30 days to respond to a request for information (34 states); accepting non-MAGI renewals through all four modalities (41 states); and extending the 90-day reconsideration period after procedural disenrollment (36 states, Figure 8).

Systems and Enrollment Processes

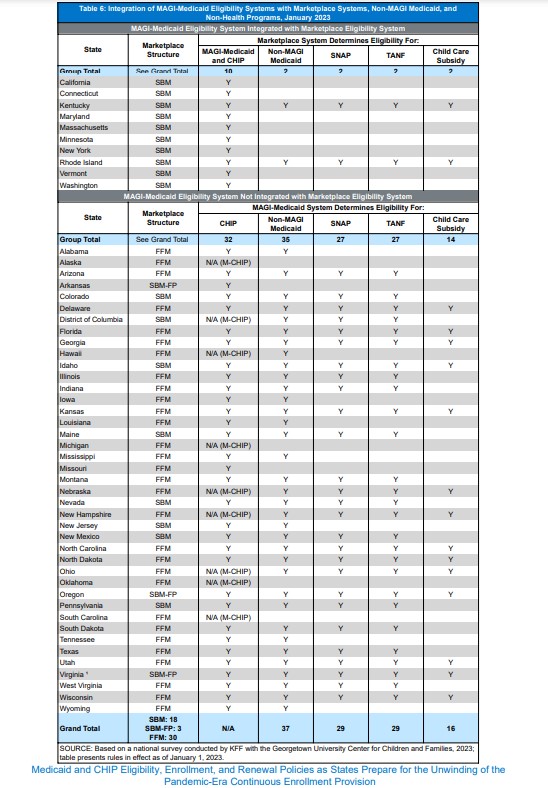

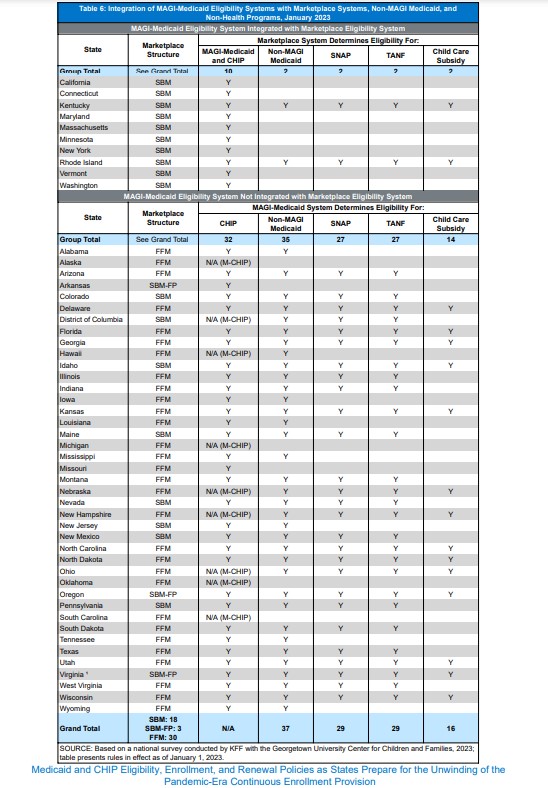

Eligibility System Integration

Some SBM states have integrated MAGI-based Medicaid and CHIP into the Marketplace eligibility and enrollment system. Of the 21 SBM states, 18 operate their own Marketplace eligibility and enrollment system while three SBM states (Arkansas, Oregon, Virginia) continue to use the federal healthcare.gov platform (SBM-FP) for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment. Of the states that operate their own Marketplace eligibility systems, ten also determine eligibility for MAGI Medicaid and CHIP (Figure 9). However, eight SBM states, along with the three SBM-FP states and 30 Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) states using healthcare.gov for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment, operate separate systems for Medicaid and CHIP (41 states in total). Having integrated Marketplace and Medicaid systems can facilitate coverage transitions for people determined ineligible for Medicaid.

Over two-thirds of all states (37) have integrated non-MAGI Medicaid and over half of the states (29) have integrated SNAP and TANF into the system used to determine eligibility for MAGI-based Medicaid and CHIP (Figure 10). These counts include South Dakota that deployed a new integrated system in 2022. Ohio became the 16th state to integrate eligibility for childcare subsidies in their Medicaid systems. Of the ten states with integrated Marketplace and MAGI-based Medicaid system, only Kentucky and Rhode Island have integrated non-MAGI Medicaid and non-health programs with their SBM systems. System integration for health and non-health programs can smooth transitions between health coverage groups and make it easier for individuals to apply for multiple assistance programs. Integrated systems can also increase administrative efficiency by aligning eligibility tasks and sharing data that is used for multiple programs, such as contact information and income.

Eligibility Verification Processes

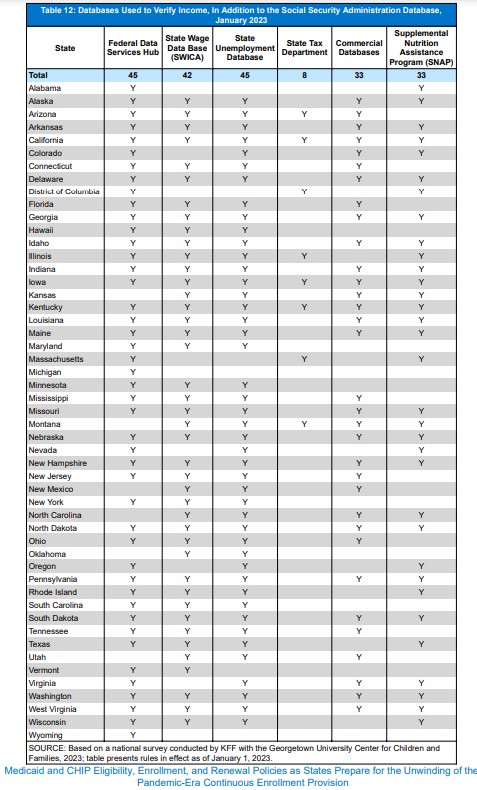

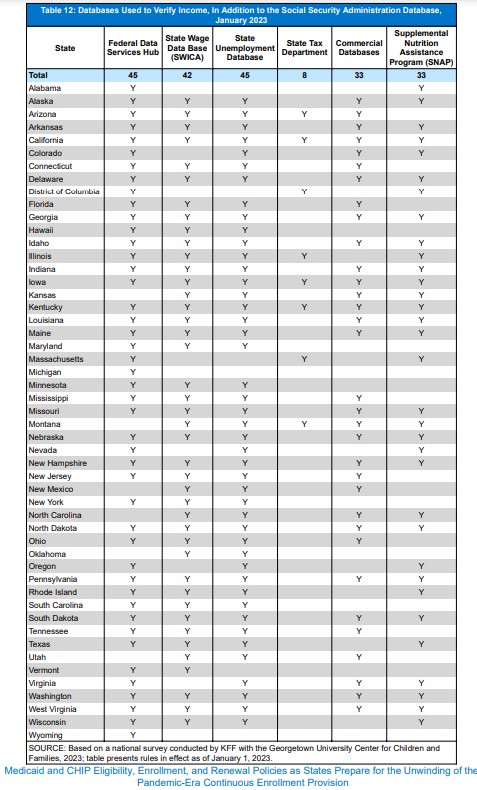

All states use electronic data matches from a variety of reliable sources to verify income eligibility at application and renewal. States have long used data linkages to the Social Security Administration (SSA) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to verify certain types of income, birthdates, and citizenship or immigration status. The ACA accelerated state use of other data sources requiring states to first attempt to verify eligibility (both income and other criteria) before collecting documentation from the individual. States must verify income, but they have the option to accept an applicant’s attestation and verify income post-enrollment, as 11 states do. At renewal, states only need to verify eligibility criteria subject to change – most often income. In addition to the SSA income data, state income sources include the Federal Data Services Hub (45 states), state wage databases, (42 states), and state unemployment databases (45 states). Two-thirds of states also use SNAP income data (33), as well as commercial databases, like TALX or the Work Number (33) that provide wage information for large employers. Eight states also use state tax department data.

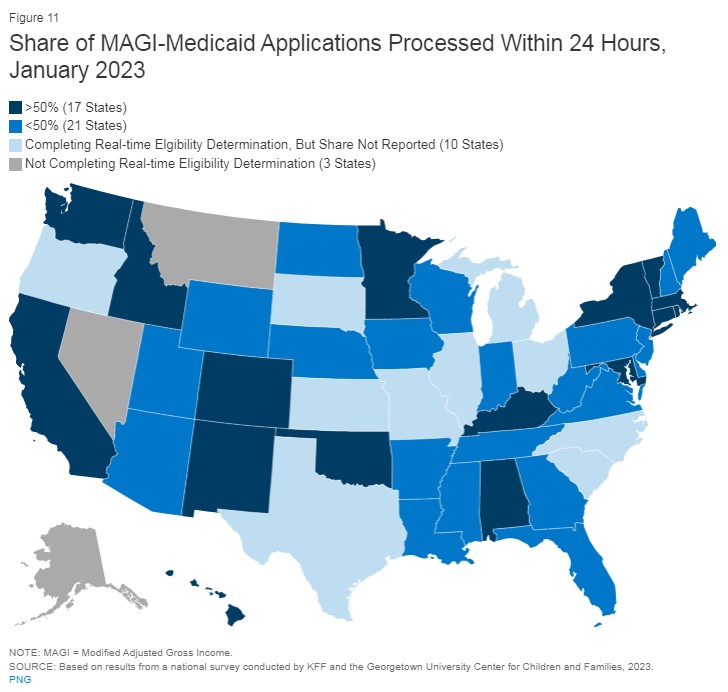

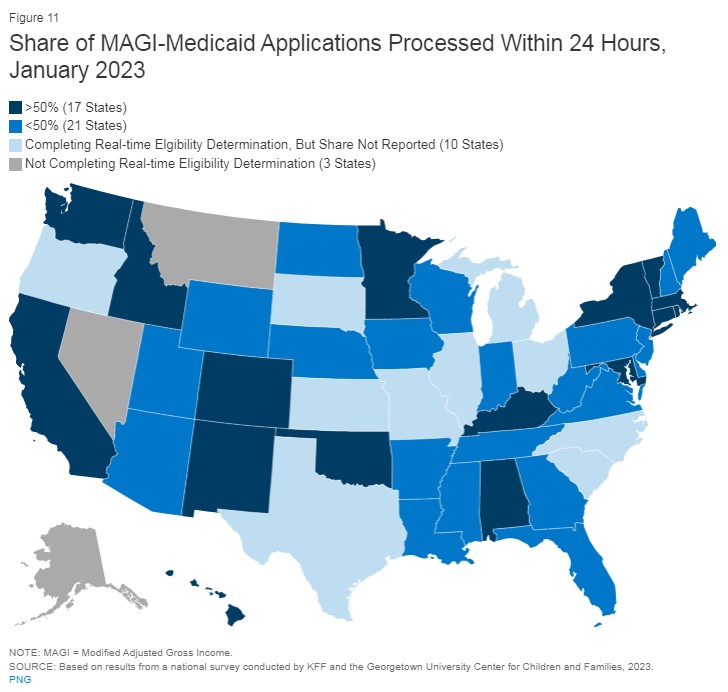

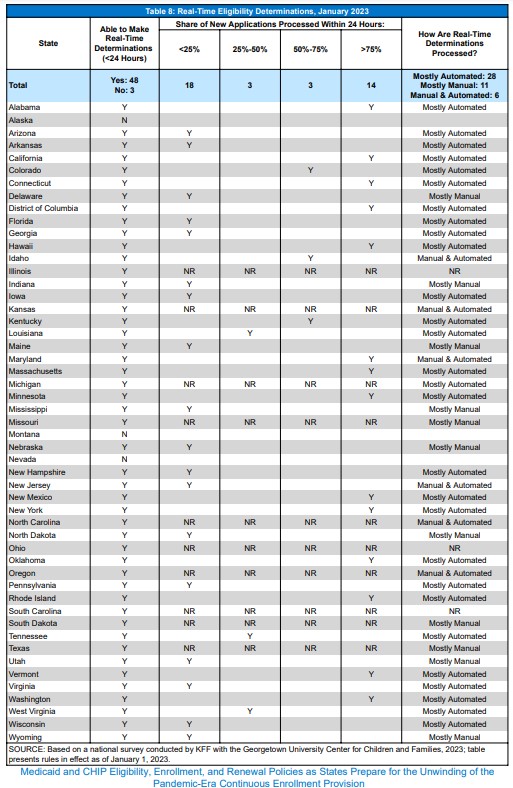

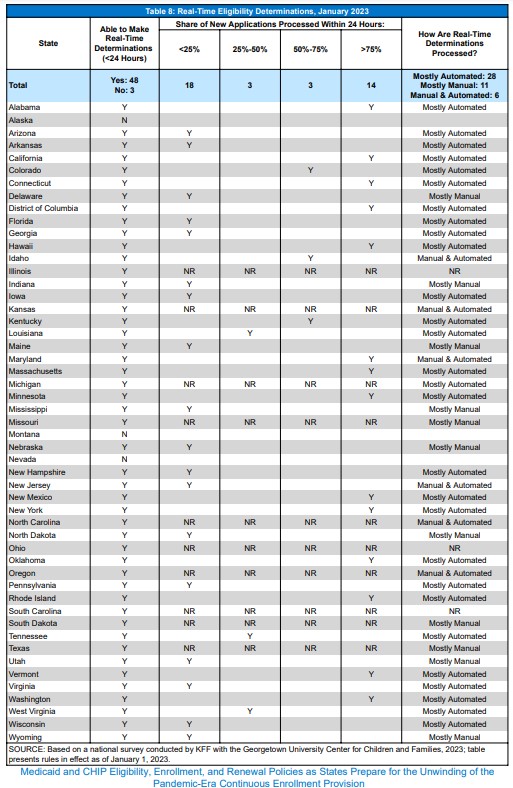

The use of electronic data enables most states to process at least a small number of applications in real-time (defined as within 24 hours); however, there is significant variation across states in the share of real-time determinations. A total of 48 states report being able to make real-time eligibility determinations, with 17 states determining eligibility for more than half of new applications within 24 hours, including 14 states that process more than 75% of applications in real time (Figure 11). Of the 48 states reporting the share of real-time determinations, 28 states indicate that most determinations are made automatically by the system. However, in 11 states, real time determinations generally require manual processing by an eligibility worker and may occur only when an individual applies in person with all documents needed to determine eligibility. In six states real-time determinations are a mix of automated and manual processes (three states did not report how real-time determinations are processed).

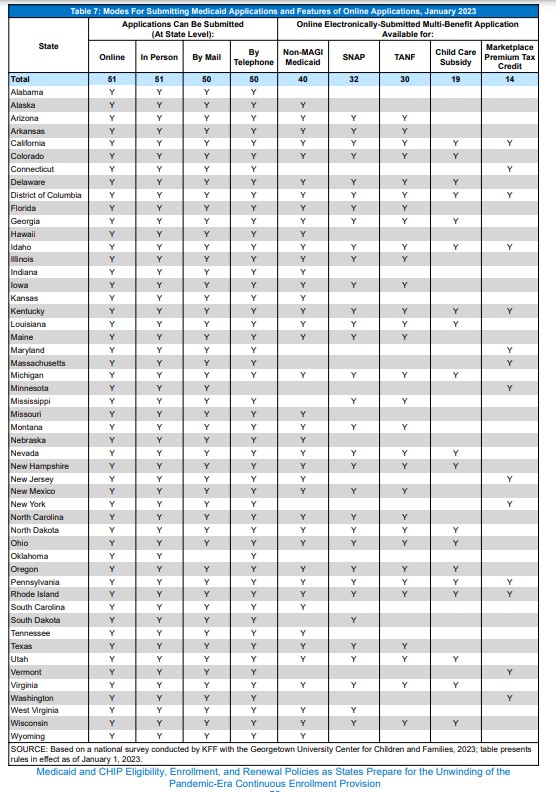

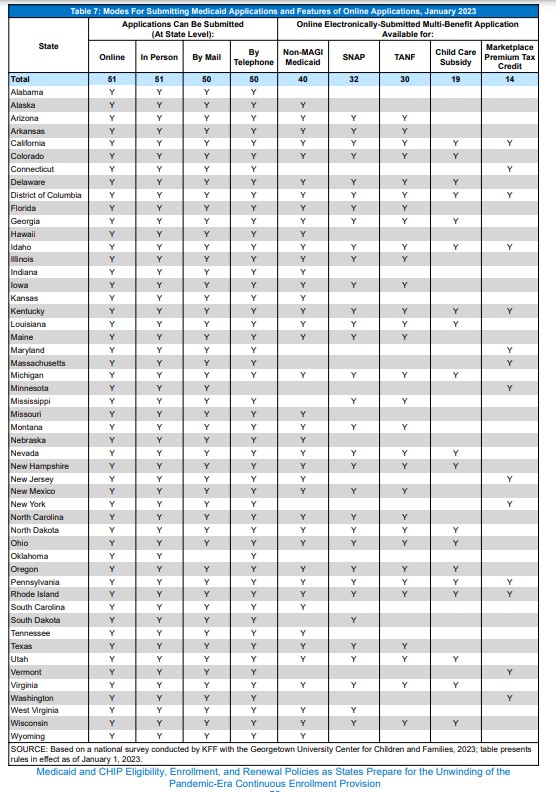

Applications, Online Accounts, and Assister Portals

In almost all states, applications can be submitted online, by telephone, in person, or by mail. Since the ACA was implemented, there has been an effort to advance Medicaid IT systems to increase administrative efficiency and accuracy while making it easy to apply for coverage. However, federal rules require states to accept applications through all four modes even in states that attempt to drive most applications through online portals and limit in-person or telephonic applications. As of January 2023, all states accept applications online and in-person, while 50 states accept telephonic applications and paper applications through the mail. CMS has been working with states on mitigation strategies that will move the states toward permanent compliance with this requirement.

States continue to add non-MAGI Medicaid and non-health programs to their Medicaid applications. Applicants are able to apply for both MAGI and non-MAGI Medicaid through a single application in 40 states. Multi-benefit applications now include SNAP in 32 states and TANF in 30 states, including Idaho, Louisiana and North Carolina that added these programs to their applications in 2022, and 19 states include childcare subsidies in their multi-benefit applications, with the District of Columbia, Louisiana, and Ohio updating their applications in 2022. Among SBM states, 14 have joint applications for Marketplace premium tax credits and Medicaid. Only Kentucky and Rhode Island have joint applications that also include non-health programs. Multi-benefit applications are more common in states that have Medicaid eligibility systems that are integrated with non-MAGI Medicaid and non-health programs. Along with integrated systems, multi-benefit applications streamline the application process for both enrollees and the state.

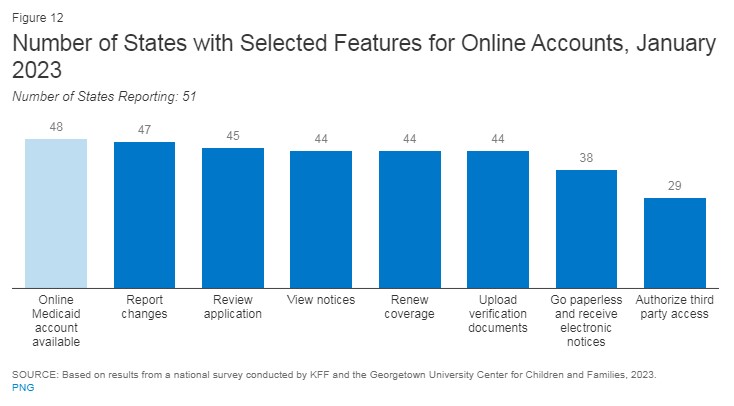

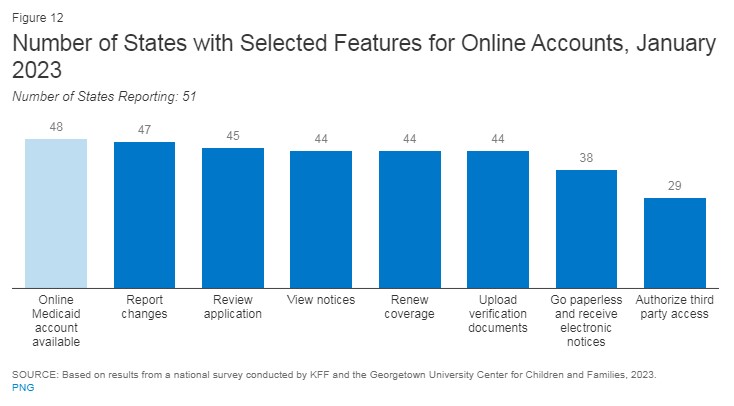

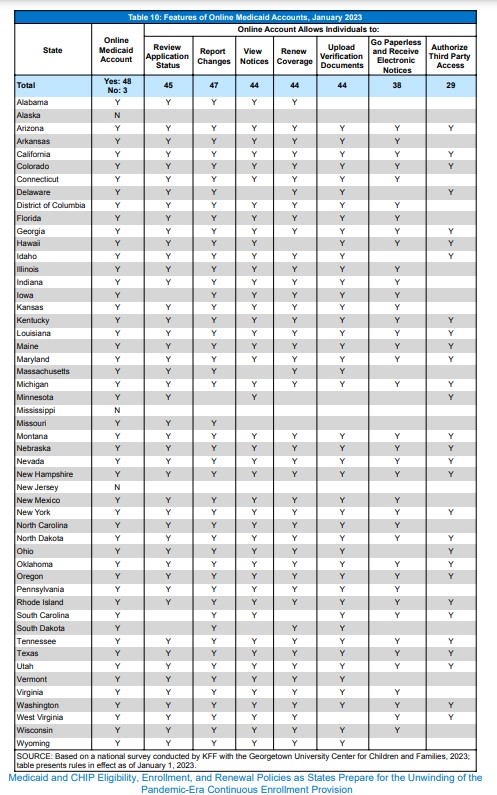

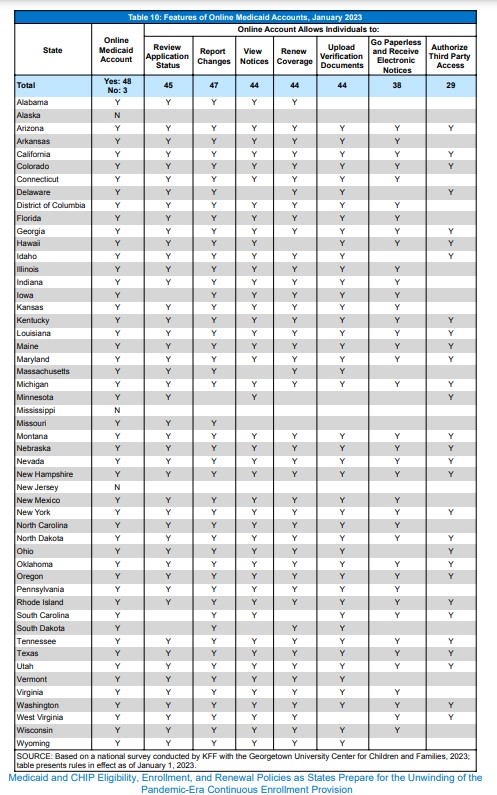

Nearly all states (48) offer online accounts for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees that make it easier for individuals to submit and access information about their coverage. Of 30 states reporting the share of enrollees with online accounts, 14 states report that more than 50% of enrollees have accounts. Most states with online accounts allow individuals to check application status (45 states); report changes (47 states); renew coverage (44 states); upload verification documents (44); and view notices (44 states). Slightly fewer states (38) permit individuals to go paperless and receive electronic notices and just over half of the states (29) allow individuals to authorize a third party to access their accounts (Figure 12).

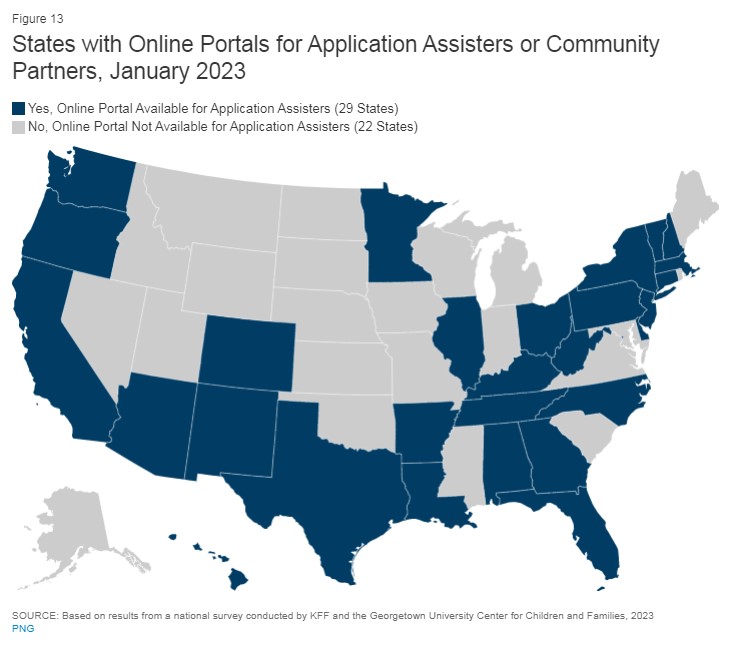

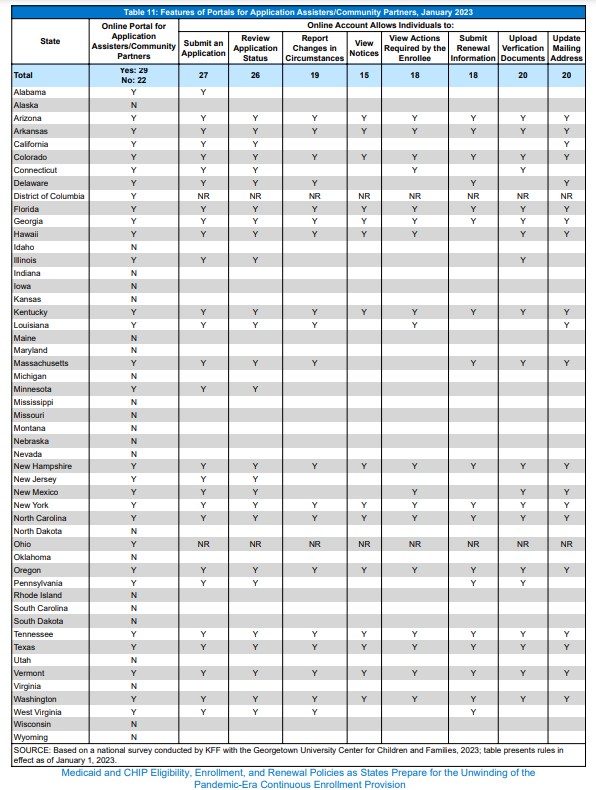

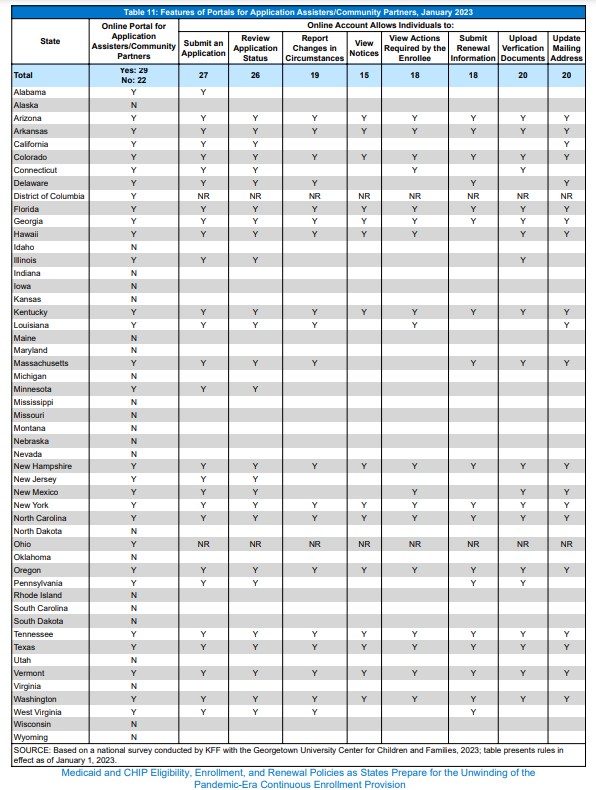

Over half of states (29) offer online portals for navigators, application assisters, and community partners to assist consumers with enrollment and renewal. Secure portals create administrative efficiencies by allowing assisters to perform administrative tasks that assist with enrollment and renewal and provide a mechanism for states to monitor assister performance. In the 27 states that reported the features available through the online portal, assisters are able to submit applications (27 states); review application status (26 states); report changes in circumstances (19 states); view notices (15 states); view pending actions (18 states); submit renewal information (18 states); upload documents (20 states); and update contact information (20 states, Figure 13).

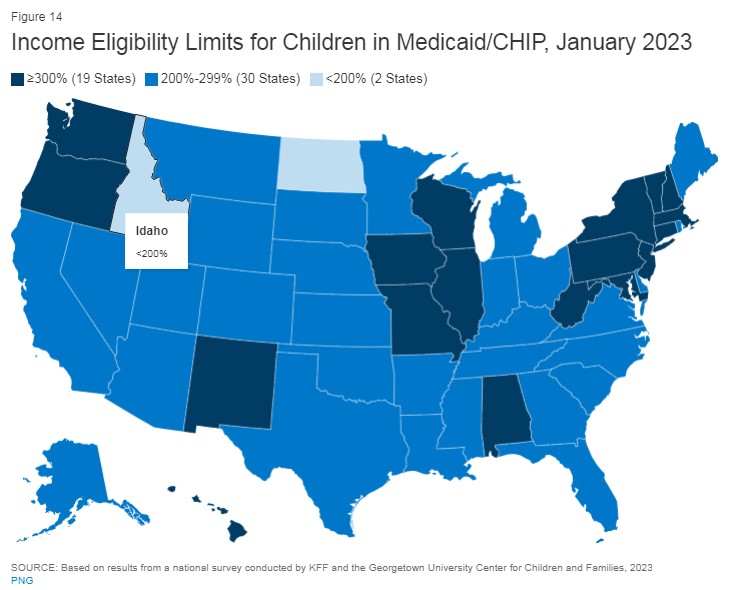

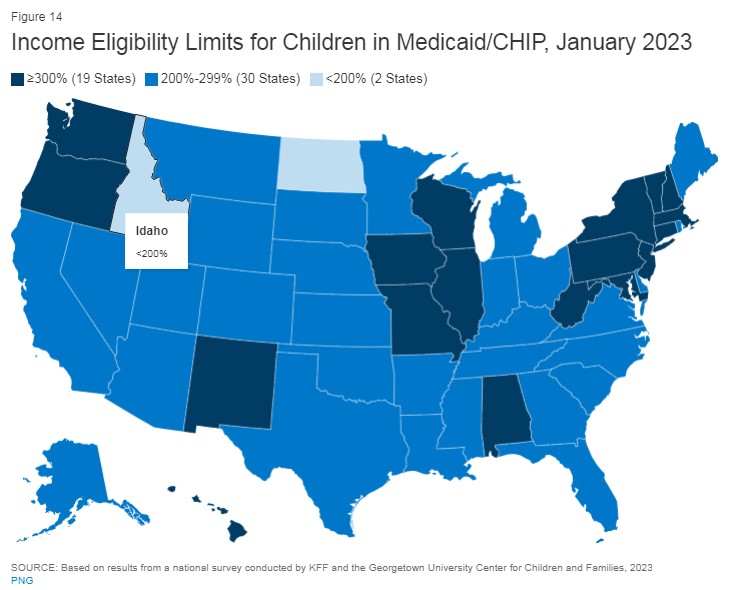

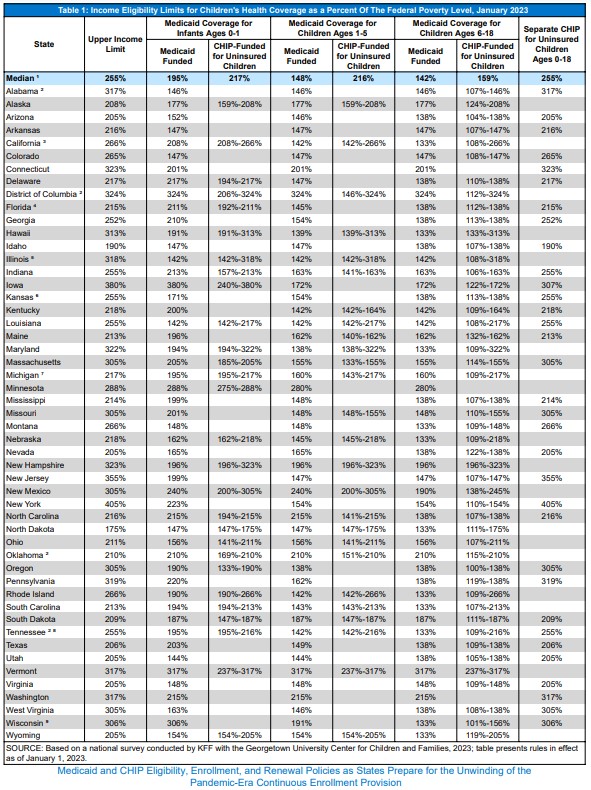

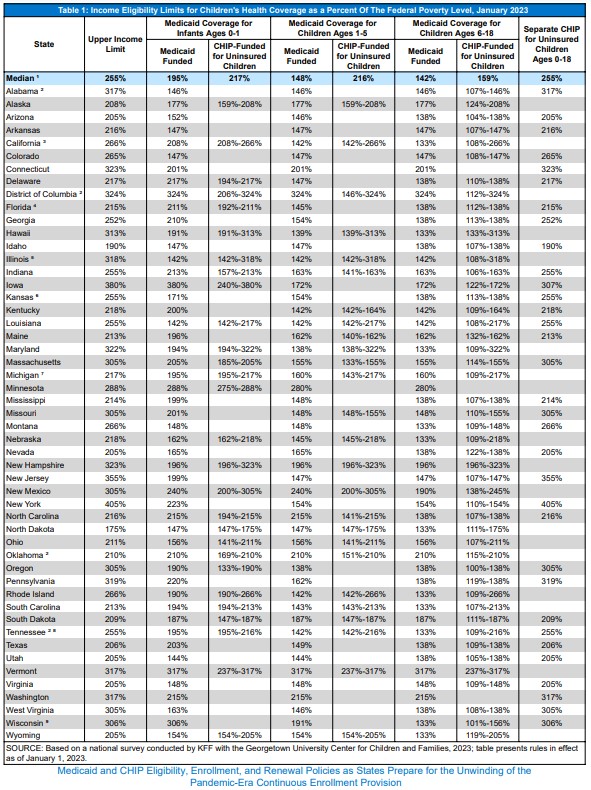

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

With enrollment standards protected in 2022, children’s upper income eligibility remained steady at a median eligibility level at 255% FPL, the highest of all eligibility groups. Eligibility levels range from a low of 175% FPL in North Dakota to a high of 405% FPL in New York. All but two states (Idaho and North Dakota) cover children at or above 200% FPL and more than a third of states (19) cover children at or above 300% FPL (Figure 14). The only change in eligibility levels for children’s coverage was in Kansas, where the legislature increased CHIP eligibility to 255% FPL in July 2022 for a twelve-month period. Illinois transitioned coverage of uninsured children eligible for CHIP from a separate CHIP program to a CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion (M-CHIP). As of January 2023, 18 states use an M-CHIP structure for their CHIP program. North Carolina plans to transition its separate CHIP program into an M-CHIP program in 2023.

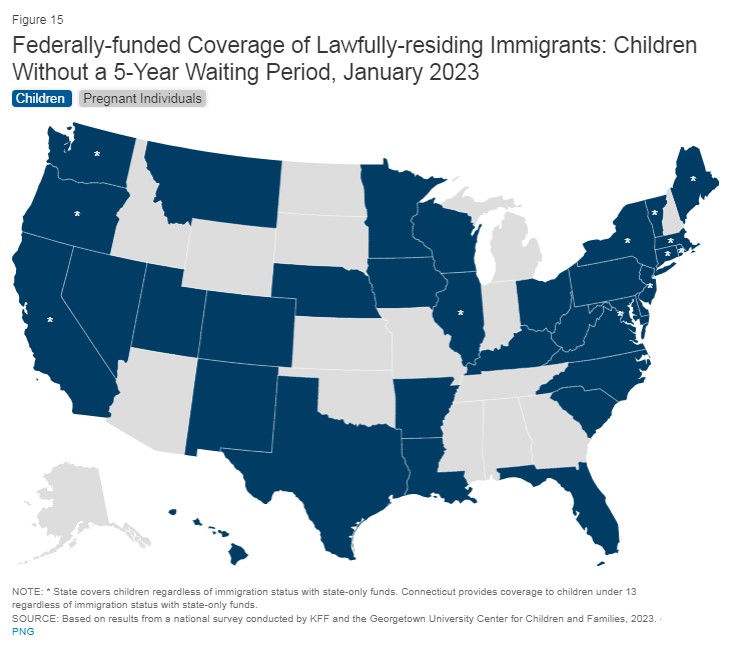

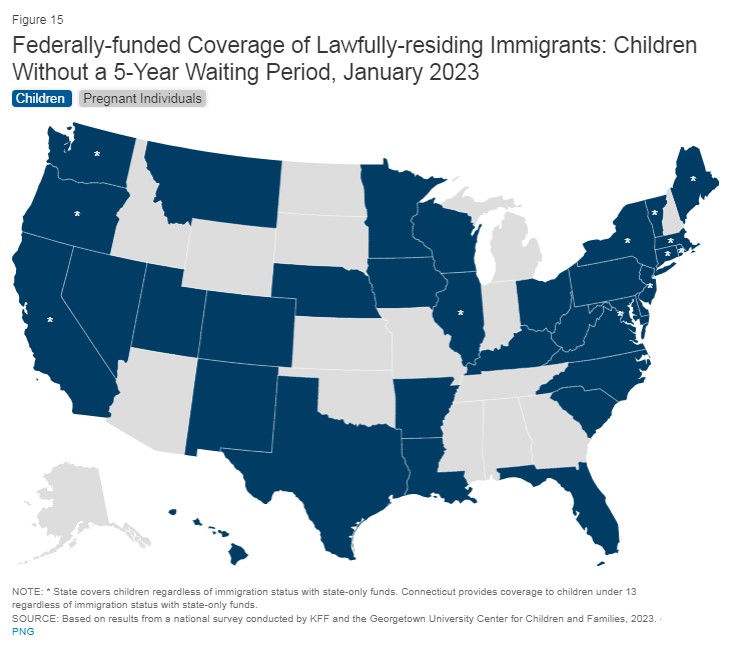

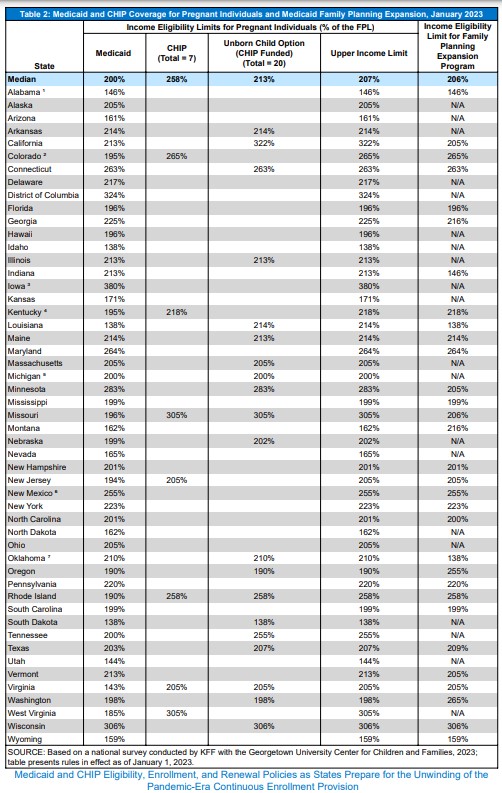

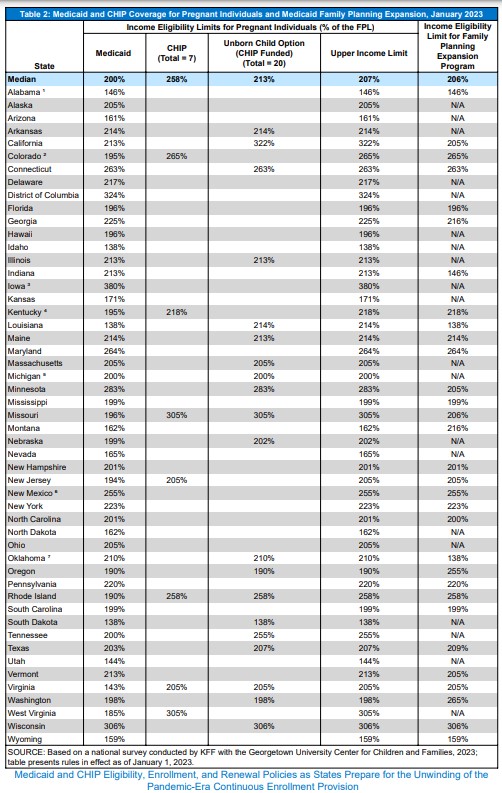

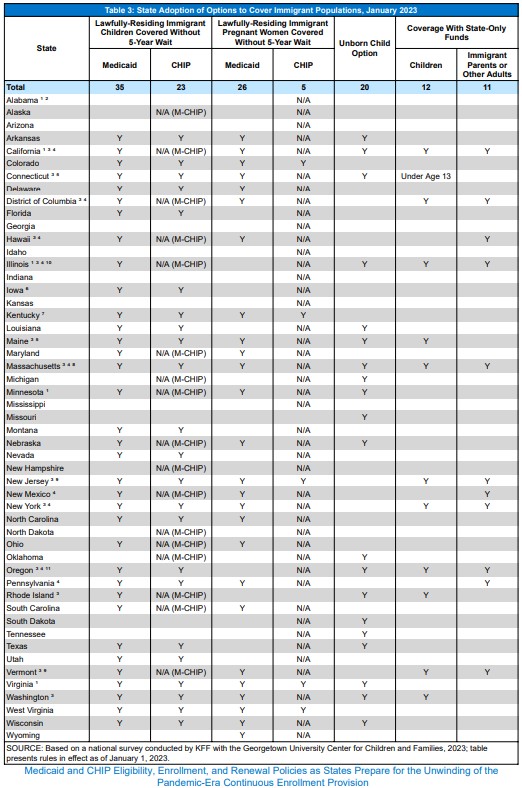

Four states took steps to expand access to pregnancy coverage, including for pregnant immigrants, increasing the median eligibility limit for pregnancy coverage in Medicaid and CHIP to 207% FPL. Most states provide pregnancy coverage at higher income levels than those for parents or other adults, ranging from a low of 138% (the federal minimum level) in Idaho and South Dakota to a high of 380% FPL in Iowa. Roughly two-thirds of states (35) cover pregnant individuals at or above 200% FPL. Oklahoma has submitted a SPA to increase its eligibility level for pregnancy coverage in Medicaid to 210% FPL, from 138% FPL previously, with a retroactive effective date of January 1, 2023. All states cover pregnant youth under age 19 in CHIP, but states that cover pregnancy in Medicaid up to 185% FPL can also use CHIP funds to expand pregnancy coverage to individuals over age 19. In July 2022, Kentucky expanded pregnancy coverage to 218% FPL through CHIP, becoming the seventh state to do so. Since CHIP’s enactment in 1997, states have had the option to provide CHIP coverage from conception to birth, known as the unborn child option, effectively extending pregnancy coverage regardless of immigration status. Connecticut and Maine adopted the option in 2022, bringing the total number of states that have adopted the option to 20 (Figure 15). Several additional states, including Colorado, Maryland, New York, and the District of Columbia, are taking steps to adopt the policy in 2023 or later. Vermont also extended pregnancy coverage regardless of immigration status using state-only funds.

As of January 2023, 40 states have adopted federally-funded options to extend coverage to some immigrant children and/or pregnant individuals without the five-year waiting period. The 2009 CHIP Reauthorization Act, or CHIPRA, offers states the option to waive the five-year waiting period for lawfully-residing children and pregnant people. In the last decade and a half, 36 states have adopted the CHIPRA option for children in Medicaid and all of those states with separate CHIP programs (23 states) cover eligible immigrant children in CHIP (Figure 15). As of January 2023, 26 states cover lawfully-residing pregnant people in Medicaid without a five-year waiting period, as do five of the seven states using CHIP to cover pregnant adults (both counts include Kentucky which adopted the policy in 2022). All states covering recent lawful residents during pregnancy, except Wyoming, have adopted the option for children as well.

States are increasingly using state-only funds to extend coverage or limited benefits to some immigrant children, pregnant individuals, and other adults who do not have federal pathways to coverage. A dozen states (12) now cover all income-eligible children regardless of immigration status, using state funds, although Connecticut only covers children under age 13. Connecticut, Maine, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Vermont extended this coverage in 2022 (Figure 15). Vermont also extended state-funded coverage to pregnant people who do not qualify for federal funding. With the permanent option to extend postpartum coverage for a full twelve months, there is growing interest in providing extended postpartum services to immigrant populations who are not eligible due to immigration status. A total of 12 states do so, with seven states (Connecticut, District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington) using state-only funds and four states (California, Illinois, Minnesota, and Virginia) using CHIP health service initiative (HSI) funding. As of January 2023, 11 states use state-only funds to cover other immigrant adults who are otherwise ineligible, including four states (Illinois, New Jersey, Oregon, and Vermont) that newly extended coverage to targeted immigrant adult groups in 2022.

In 2022, South Dakota voters passed a ballot initiative to adopt the ACA Medicaid adult expansion, leaving 11 states where a coverage gap will remain for low-income adults. South Dakota will implement Medicaid expansion in July 2023, making it the seventh state where voters have approved ballot initiatives to adopt Medicaid expansion. North Carolina is now poised to become the 41st state to adopt Medicaid expansion after legislators in the state reached a deal that is expected to be voted on soon. As of January 2023, 39 states cover parents and adults without dependent children with incomes at least up to 138% FPL (the FPL is $14,580 per year for an individual; $24,860 for a family of three in 2023). When Medicaid expansion coverage began in January 2014, only half of the states (26) adopted the option. Following implementation in South Dakota, the total number of expansion states will increase to 40.

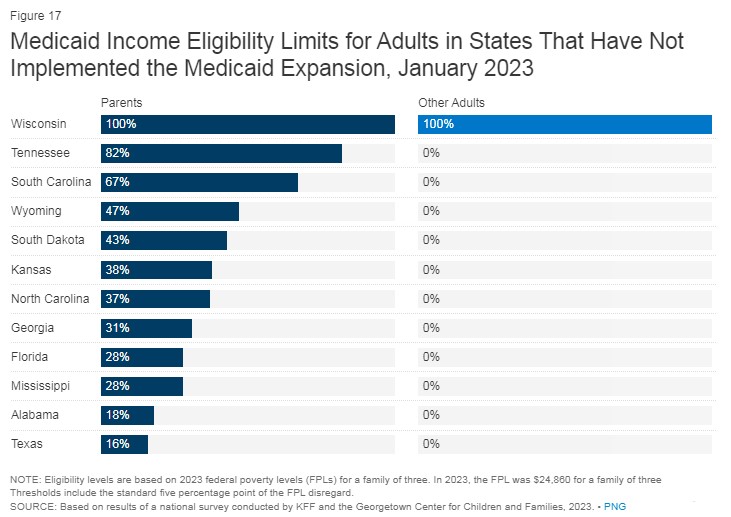

Eligibility remains extremely low in the states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion as of January 2023 with the median income eligibility dropping to 37% FPL (Figures 16 and 17). Eight non-expansion states as of January 2023 (Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming) base income eligibility on dollar thresholds that are not routinely updated. Mississippi was the only state of those seven to update its fixed dollar threshold for a family of three from $384 per month in 2022 to $480 per month in 2023. Over time, the equivalent federal poverty level eligibility level decreases as the federal poverty threshold is adjusted upward to account for inflation. In 2023, the FPLs rose significantly from between 7.3% and 8.4% depending on household size, so the erosion is more evident. For example, Tennessee’s parent eligibility declined from 88% FPL in 2022 to 82% FPL in 2023. The median eligibility level for parents and caretakers in the 12 non-expansion states is now 37% FPL ($9,198 annually for a family of three), ranging from a low of 16% FPL in Texas to 100% FPL in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state that provides coverage to adults without dependent children, aligning eligibility with that for parents at 100% FPL, through a waiver.

The median eligibility level for family planning services held steady at 206% FPL, but eligibility levels range from 138% FPL in Louisiana and Oklahoma to a high of 306% FPL in Wisconsin. In July 2022, Colorado became the 31st state to use federal funds, through a state plan option or waiver, to provide family planning only services to people who do not qualify for full Medicaid through another pathway.

Continuous Eligibility Policies

As of January 2023, 33 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility for some or all children in Medicaid and/or CHIP; all states will be required to do so starting in 2024. Continuous eligibility is more prevalent in CHIP with 24 states of the 33 states with separate CHIP programs providing a full year of coverage compared to 26 of the 51 Medicaid programs (Figure 18). These counts include states that provide 12-month continuous coverage to an age-limited group (Florida, Indiana, and Pennsylvania). The CAA requires all states to provide 12-month continuous coverage to all children in Medicaid and CHIP, beginning January 1, 2024. Oregon became the first state to receive approval to cover children continuously until their sixth birthday; three other states, California, New Mexico, and Washington, have similar plans. Oregon also received approval to provide two-year continuous eligibility for older children. Illinois is developing a proposal to provide two-year continuous eligibility for all children.

More than two-thirds of states (37) have extended or plan to extend postpartum coverage following pregnancy for 12 months, as of January 2023. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 gave states the option to provide 12-month postpartum coverage in Medicaid and CHIP via a state plan amendment (SPA) for five years; however, the CAA made the option permanent. As of January 2023, 29 states have implemented the option, with an additional eight states in various stages of seeking approval to do so (Figure 19). The quick take-up of this option, with 37 states moving forward in less than two years and additional states currently debating legislation to adopt the coverage extension, is a reflection of the country’s increased focus on maternal health and health disparities.

Several states have received Section 1115 waiver authority to provide continuous eligibility to adults. Oregon became the first state to receive approval to provide two-year continuous eligibility for all adults. New York provides 12-month continuous eligibility for all adults, while Kansas covers section 1931 parents and caretakers for a full year under waiver authority. Massachusetts provides 12-month continuous eligibility for individuals released from correctional settings and two-year continuous eligibility for people who are chronically homeless. Utah also provides 12-month continuous eligibility for a targeted group of very low-income adults.

Waiting Periods and Premiums for Children

Some states continue to require that children be uninsured for a period of time before enrolling in CHIP. CHIP funding can only be used to cover “uninsured” children. States are required to take steps to discourage the substitution of CHIP for private group insurance and early on many states chose to do so by requiring a period of time that a child must be uninsured before enrolling in CHIP. However, the ACA introduced several federally required exemptions to the waiting periods, such as loss of employer coverage or job loss, that has led states to drop their waiting periods because most children qualify for an exemption. The ACA also limited waiting periods to less than 90 days. Two states (Indiana and Maine) waived CHIP waiting periods during the pandemic, and Maine has decided not to reinstate. Going forward nine states (Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah) will continue to impose waiting periods ranging from one month to 90 days.

Two-thirds of states (19 of 30 states) that charge premiums or enrollment fees to children waived those charges during the PHE. States may not charge premiums to Medicaid enrollees with income below 150% FPL but have more flexibility in charging premiums or enrollment fees to children in CHIP. In 2020, 26 states charged quarterly or monthly premiums and four states required enrollment fees. Of the 30 states charging premiums or enrollment fees, 19 states suspended premiums temporarily during the PHE. Six states (California, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, New Jersey, and North Carolina) do not plan to resume premiums after the PHE ends or have already eliminated them and New York eliminated the premium tier for the lowest-income children on CHIP. About half of the states that plan to resume premiums will do so at the end of the PHE; others plan to wait a few months or until the end of the unwinding period.

Looking Ahead

States are moving from planning for the end of the continuous enrollment provision to implementation of their unwinding plans, but the impact of the unwinding will vary by state. Passage of the CAA propelled states into the final planning stages, with several states moving as quickly as allowed to initiate the unwinding period. How the unwinding impacts Medicaid enrollees and state spending will vary significantly from state to state depending on each state’s systems capabilities, including ex parte renewal rates; communications strategies; staff capacity; and operational policies that make it easier for people to stay enrolled.

After achieving historically low rates of uninsurance, largely spurred by the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision as well as enhanced subsidies in the ACA marketplace, it is likely that the uninsured rate will increase as states resume Medicaid disenrollments. Most people who are disenrolled from Medicaid because they are no longer eligible should have a path to other coverage options through the Marketplaces or an employer, but even with zero premium ACA plans available for some, affordability may remain a barrier for others. Enhancing systems to facilitate coverage transitions and increasing the availability of consumer assistance can help increase the number of people who gain other coverage. Still, disenrollments for procedural reasons are expected to be high. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) estimated that 45% of people disenrolled during the unwinding will lose coverage despite remaining eligible, which will disproportionately impact children and people of color. Boosting staff resources, actively monitoring the unwinding to identify issues, and rapidly responding to systemic or recurring problems can help avoid procedural disenrollments that lead to coverage losses.

While the Biden Administration works to finalize rules and policy to help promote and expand coverage, Republicans in Congress may push for cuts to Medicaid. The HHS Regulatory Agenda for 2023 includes finalizing rule changes relating to eligibility and enrollment, access and managed care, mandatory reporting of the child core set of healthcare quality measures, and anti-discrimination. The eligibility and enrollment rule would strengthen coordination between Medicaid and CHIP; require states to improve processes for handling returned mail; set new time standards for processing applications and renewals; and align non-MAGI and MAGI application and renewal policies. While the effective dates of the requirements in the eligibility and enrollment rule may be staggered over time, states will be challenged to implement significant changes amid the unwinding. Other rules likely to be finalized will also require the attention of Medicaid leadership at a pivotal time for the agency. At the same time, Congressional debate over the debt ceiling has given rise to talk of cuts to Medicaid and other assistance programs. Interest in putting restrictions on Medicaid enrollment, such as work requirements, have resurfaced, as well as strategies to slow the growth in Medicaid spending that largely shift increasing costs on the states by putting constraints on federal funding. How serious this debate is remains to be seen.

Table 1 Notes

January 2023 income limits are reported as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). The 2023

FPL for a family of three is $24,860. The reported levels reflect Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI)-

converted income standards and include a disregard equal to five percentage points of the FPL applied at

the highest income level for Medicaid and separate CHIP coverage. In states without a separate CHIP

program, the disregard is added to the highest Medicaid or the CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion limit. In

states with a separate CHIP program, the disregard is applied to the highest Medicaid or CHIP-funded

Medicaid expansion limit (M-CHIP) as well as to the upper eligibility limit of the separate CHIP program.

Because CHIP funding is limited to uninsured children, in states that have a higher eligibility limit for their

CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion than regular Medicaid, there may be a small number of children who

have another source of coverage that would be eligible for Medicaid when the 5-percentage point

disregard is applied, which is not reflected in the table.

States may use Title XXI CHIP funds to cover children through CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion

programs (M-CHIP) and/or separate child health insurance programs for children not eligible for Medicaid.

Use of Title XXI CHIP funds is limited to uninsured children. The Medicaid income eligibility levels listed

indicate thresholds for children covered with Title XIX Medicaid funds and uninsured children covered

with Title XXI funds through CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion programs. To be eligible in the infant

category, a child has not yet reached his or her first birthday; to be eligible in the 1-5 category, the child is

age one or older, but has not yet reached his or her sixth birthday; and to be eligible in the 6-18 category,

the child is age six or older, but has not yet reached his or her 19th birthday.

The states noted use federal CHIP funds to operate separate child health insurance programs for children

not eligible for Medicaid. Such programs may either provide benefits similar to Medicaid or a somewhat

more limited benefit package. They also may impose premiums or other cost sharing obligations on some

or all families with eligible children. Unlike Medicaid, which allows states to cover 19 and 20 years as

children, CHIP coverage is limited to uninsured children under the age of 19.

Footnotes

1. Medians for children are based on the upper income limit for Medicaid and CHIP combined.

2. Alabama, the District of Columbia, Oklahoma, and Tennessee have different lower bounds for

adolescents in Title XXI funded Medicaid expansions depending on age. The lower bound for Title

XXI funded Medicaid is 18% for children ages 14 through 18 in Alabama, 63% for children ages 15

through 18 in the District of Columbia, 69% for children ages 14 through 18 in Oklahoma, and 29% for

children ages 14 through 18 in Tennessee.

3. In California, children with higher incomes are eligible for separate CHIP coverage in certain counties.

4. In Florida, all infants ages 0 to 1 are covered in Medicaid. Florida operates three separate CHIP

programs: MediKids covers children ages 1 through 4; Healthy Kids covers children ages 5 through

18; and the Children’s Medical Services Managed Care Plan serves children with special health care

needs from birth through age 21. In Florida, families can buy in to Healthy Kids for children ages 5-19

and to MediKids for children ages 1 to 4.

5. Illinois transitioned its separate CHIP program to a Medicaid expansion program in July 2022.

6. In Kansas, legislation was passed in 2022 to increase the CHIP eligibility income level to 255% of the

current federal poverty level for a twelve-month period. Prior to the change, eligibility for children in

the separate CHIP program was based on a dollar-based income level equal to 250% FPL in 2008.

As a fixed dollar amount, the equivalent FPL level erodes over time when the poverty threshold is

adjusted for inflation. In January 2022, the equivalent FPL level was 230% FPL.

7. Michigan provides CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion coverage to children with incomes between

212% FPL to 400% FPL affected by the Flint water crisis.

8. In Tennessee, Title XXI funds are used for two programs, TennCare Standard (a Medicaid expansion

program) and CoverKids (a separate CHIP program). TennCare Standard provides Medicaid

coverage to uninsured children who lose eligibility under TennCare (Medicaid), have no access to

insurance, and have family income below 216% FPL or are medically eligible.

9. In Wisconsin, children are not eligible for its separate CHIP program if they have access to job-based

health insurance coverage where the employer covers at least 80% of the cost.

Table 2 Notes

January 2023 income limits reflect Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI)-converted income standards

and include a disregard equal to five percentage points of the federal poverty level (FPL). The FPL for a

family of three is $24,860 as of 2023.

The unborn child option permits states to cover “targeted low-income children” from conception to birth in

CHIP, regardless of the pregnant person’s immigration status.

The totals in column headers indicate that the option only applies to the limited number of states that

have adopted the coverage pathway. As of January 2023, seven states use CHIP funding to cover

pregnant individuals and 20 states provide coverage through the unborn child option.

Some states also use federal funds under a state option or waiver to provide family planning services to

individuals who do not qualify for full Medicaid benefits.

Footnotes

1. Alabama has a pilot program for the unborn child option, providing coverage up to 317% FPL in three

counties.

2. Colorado began providing family planning services for individuals with incomes up to 260% FPL,

effective July 2022.

3. Iowa has a state-funded family planning program for women with incomes up to 300% FPL who lose

Medicaid at the end of the postpartum period.

4. Kentucky began covering pregnant adults with incomes up to 218% FPL through CHIP in July 2022.

5. Michigan provides coverage to pregnant individuals with incomes up to 400% FPL affected by the

Flint water crisis.

6. In New Mexico, family planning coverage is limited to individuals age 50 and younger without health

insurance.

7. Oklahoma has submitted a state plan amendment (SPA) to increase the eligibility level for pregnant

individuals in Medicaid to 210% FPL. The SPA would be effective retroactive to January 1, 2023. The

state also offers a premium assistance program through its Insure Oklahoma program to pregnant

people with incomes up to 205% FPL who have access to employer sponsored insurance.

Table 3 Notes

This table reflects state coverage of immigrant populations using federal or state funds. In some cases,

coverage is limited to targeted groups, such as lawfully present immigrants who are in the five-year

waiting period for Medicaid coverage, or the coverage provides more limited benefits than Medicaid.

States have the option to provide coverage for immigrant children and pregnant individuals who have

been lawfully residing in the U.S. for less than five years, otherwise known as the Immigrant Children’s

Health Improvement Act (ICHIA) option. States can also adopt the unborn child option in CHIP. The

unborn child option permits states to cover “targeted low-income children” from conception to birth in

CHIP, regardless of the pregnant person’s immigration status. Some states use state-only funds to

provide coverage for immigrant children or adults.

N/A (M-CHIP) – state does not operate a separate CHIP program for uninsured children

Footnotes

1. Alabama, California, Illinois, Minnesota, and Virginia use a CHIP Health Services Initiative (HSI) to

provide a period of extended postpartum coverage, ranging from 60 days to 12 months, to certain

immigrant pregnant individuals not otherwise eligible due to immigration status.

2. Alabama has a pilot program for the unborn child option, providing coverage up to 317% FPL in three

counties and uses a CHIP HSI to provide postpartum coverage for this group.

3. California, the District of Columbia, Illinois, New York, Oregon, and Washington cover all incomeeligible children, regardless of immigration status using state-only funds, and Maine, New Jersey,

Rhode Island, and Vermont added this coverage in 2022. Connecticut also began covering all

children under the age of 13.

4. California, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York,

Pennsylvania, and Oregon cover some income-eligible adults who are not otherwise eligible due to

immigration status. In some cases, the coverage is limited to targeted groups or the coverage

provides more limited benefits than Medicaid.

5. In 2022, Connecticut and Maine adopted the unborn child option.

6. Iowa covers immigrant children in foster care or with a subsidized adoption or guardianship

agreement with state-only funds and limited emergency services.

7. Kentucky began using federal funding to cover lawfully residing pregnant immigrants in Medicaid and

CHIP in 2022.

8. Massachusetts covers uninsured children who do not qualify for other MassHealth coverage (other

than MassHealth Limited) because of immigration status using state-only funds under the Children’s

Medical Security Program and other programs. The Children’s Medical Security plan provides

preventive and primary medical, dental, mental health and substance use disorder, and pharmacy

services.

9. In 2022, New Jersey and Vermont began using state-only funds to provide pregnancy coverage or

some pregnancy-related services for individuals who are not otherwise eligible for coverage.

10. Illinois began covering adults ages 42 to 54 who are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status

in 2022 using state only funds. The state had previously expanded coverage to adults age 55 and

above regardless of immigration status.

11. Oregon began using state-only funds to cover adults ages 19 through 25 and age 55 and older who

are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status in 2022.

Table 4 Notes

January 2023 income limits reflect Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI)-converted income standards

and include a disregard equal to five percentage points of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) applied to the

highest eligibility limit for each group. In some states, eligibility limits for Section 1931 parents are based

on a dollar threshold. The values listed represent the truncated FPL equivalents calculated from these

dollar limits. Eligibility levels for parents are presented as a percentage of the 2023 FPL for a family of

three, which is $24,860. Eligibility limits for single adults without dependent children are presented as a

percentage of the 2023 FPL for an individual, which is $14,580.

Footnotes

1. Group and all state median values are truncated.

2. In Alaska, the dollar threshold is updated every January 1 based on the CPI-U plus an adjustment for

annual dividend payments to Alaska residents.

3. In Illinois, traditional 1931 Medicaid coverage is based on a dollar threshold tied to TANF levels.

Parents are also covered up to 133% FPL based on prior waiver eligibility and are not considered

Section VIII expansion adults.

4. In Massachusetts, the state’s Section 1115 waiver also authorizes MassHealth coverage for HIVpositive individuals with incomes up to 200% FPL and for adults with disabilities with no income limit,

provided that they have either met a one-time deductible or are working disabled adults.

5. Minnesota and New York have implemented Basic Health Programs (BHPs) established by the

Affordable Care Act (ACA) for adults with incomes between 138%-200% FPL.

6. In Oklahoma, individuals working for certain qualified employers with incomes at or below 222% FPL

are eligible for premium assistance for employer-sponsored insurance.

7. South Dakota voters approved Medicaid ballot expansion measures in November 2022 and will

implement the expansion implementation in July 2023.

8. In Texas, the income limit for parents and other caretaker relatives is based on monthly dollar

amounts which differ depending on family size and whether there is one or two parents in the family.

The eligibility level shown is for a single parent household and a family size of three.

9. In Virginia, eligibility levels for 1931 parents vary by region. The value shown is the eligibility level for

Region 2, the most populous region.

10. Wisconsin covers adults up to 100% FPL in Medicaid but did not adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion.

Table 5 Notes

All states are required to maintain continuous enrollment for almost all Medicaid enrollees through March

31, 2023. Under normal operations states have had the option to provide 12-month continuous eligibility

to children in Medicaid and/or CHIP through a state plan amendment. However, beginning January 1,

2024, states will be required to implement continuous eligibility for all children in Medicaid and CHIP.

Continuous eligibility provides coverage to children in Medicaid and/or CHIP for a full twelve months

unless the child ages out, moves out of state, voluntarily withdraws, or does not make premium

payments. Some states have adopted continuous eligibility for certain adults through a section 1115

waiver.

Footnotes

1. In Florida, children in Medicaid under the age of 5 receive 12-month continuous eligibility while

children ages five and older receive six months of continuous eligibility.

2. Indiana provides 12-month continuous eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP to children under age 3.

3. In 2022, Massachusetts adopted continuous eligibility for a targeted group of adults. The state

provides 12-month continuous eligibility to Medicaid-eligible youth and adults following release from a

correctional institution and 24 months of continuous eligibility for individuals under 65 who are

experiencing homelessness.

4. Montana eliminated 12-month continuous eligibility for section 1931 parents in March 2022. The state

had previously eliminated 12-month continuous eligibility for expansion adults through a separate

section 1115 waiver. The state is continuing to provide continuous enrollment to all individuals as

required until the end of the continuous enrollment provision.

5. Oregon has been approved to provide multiple years of continuous eligibility to children ages zero

through five. The state has also adopted two years of continuous eligibility for all individuals age six

and older.

6. Pennsylvania provides continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid under age 4.

7. Texas provides 12-month continuous eligibility to children in CHIP with income up to 185% FPL.

8. Utah provides continuous eligibility for adults with incomes between 0-5% FPL who are experiencing

homelessness, substance use disorder, or mental health disorder.

Table 6 Notes

The table is first grouped by State-based Marketplaces (SBMs) with MAGI-Medicaid and CHIP integrated

into the Marketplace eligibility system, and then by all other states with Medicaid eligibility systems that

are not integrated with the Marketplace, regardless of Marketplace structure. It indicates whether a state

operates its own State-based Marketplace (SBM), established a State-based Marketplace that uses

Healthcare.gov, the federal eligibility and enrollment platform, (SBM-FP), or has elected to use the

Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM). SBM states are responsible for performing all Marketplace

functions, except for SBM-FP states that rely on the Healthcare.gov for application processing and certain