How Brain Health Could Affect Your Finances

How to prepare for the expense of potential cognitive decline

The costs associated with an unhealthy brain can be significant. In addition to medical costs, other areas of expenses may include caregiving, medication, and housing needs. We’ll outline potential costs in each of these areas, but first, let’s define the difference between dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The difference between Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same thing. Dementia is a general term that describes a group of symptoms affecting memory, thinking, and social abilities. It is a progressive condition that affects cognitive functioning, leading to a decline in memory, language, problem-solving, and other cognitive abilities.

Alzheimer’s disease is a specific type of dementia, accounting for about 60-80% of all cases. It is a degenerative brain disorder that gradually affects memory, thinking, and behavior. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles in the brain, which interfere with the communication between brain cells and eventually cause their death. Next, we’ll look at some trends related to the cost of an unhealthy brain.

Trends of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease

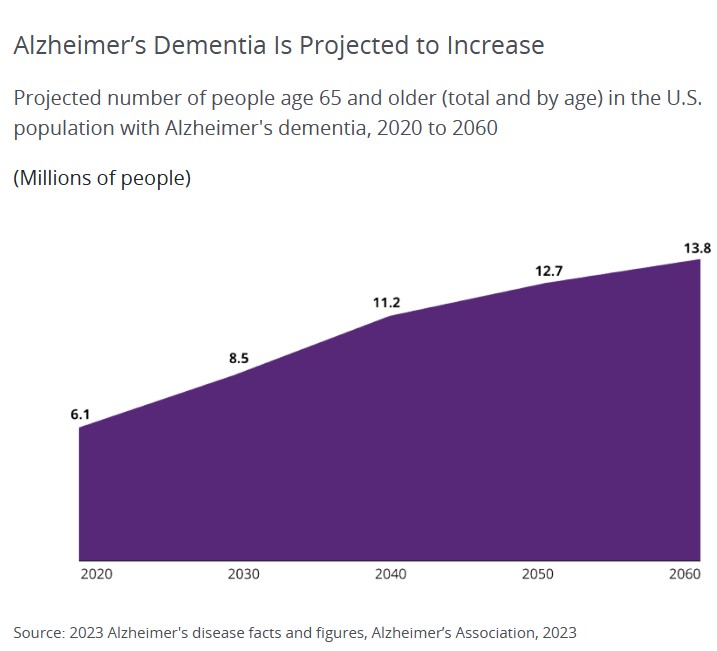

- Alzheimer’s disease is on the rise (See graph below). Because increasing age is the predominant risk factor for Alzheimer’s dementia, as the number and proportion of older Americans grows rapidly, so too will the numbers of new and existing cases of Alzheimer’s dementia.

- People 65 and older survive an average of four to eight years after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, yet some live as long as 20 years with the disease1

- Changes in the brain may begin a decade or more before symptoms appear

How Brain Health Affects Your Finances

To understand the potential financial needs during the course of Alzheimer’s disease, we need to consider all the costs we might face now and in the future. Since Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, the type and level of care needed will intensify over time.

The more financial planning that can be done soon after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, the better prepared one will be for financial issues and expenses—especially while people can still make financial and caregiving decisions for themselves.

Medication

The cost of medication for Alzheimer’s disease can vary depending on several factors, such as the type and dosage of medication, the frequency of use, the duration of treatment, and the location of the patient.A 2012 Consumer Reports Study estimated the annual cost of Alzheimer’s prescriptions could range from $2,124 to $4,800.2 However, a new drug, Aduhelm, which aims not to cure the disease but instead to slow some of the diseases’ debilitating symptoms, is priced at approximately $28,000 per year.3 Medicare typically covers 80% of the cost of medication. For just that one drug, patients would pay 20% of the cost—$5,600 per year. Medicare has limited coverage for this medication to beneficiaries enrolled in clinical trials.

Caregiving

Initially, a person with a dementia diagnosis can live independently. Often, care is provided by family and friends. But as the disease progresses, full-time care from a home-health aid (a person hired to help with basic daily activities and physical care, or require assistance with shopping, cooking, or paying bills) may be needed.A home health aide can help with caregiving. They help those who live in their homes and offer more extensive health and personal care than friends or family are able to provide, e.g., help with bathing, dressing, grooming, preparing meals, administering medications, monitoring vital signs, and performing light housework. The annual cost for a home health aide is $61,776 (based on 44 hrs. per week).4

Housing

During the middle stages of Alzheimer’s, it becomes necessary to provide 24-hour supervision to keep the person with dementia safe. As the disease progresses into the late-stages, around-the-clock care requirements become more intensive.Making the decision to move into a long-term care facility, e.g., assisted-living or nursing-home care, may be very difficult, but it’s not always possible to continue providing the level of care needed at home.

The cost of long-term care facilities can range from $50,000 to over $150,000 per year (see graph below).4,5

Medicare covers up to 100 days of “skilled nursing care” per illness, but there are a number of requirements that must be met before the nursing home stay will be covered. The result of these requirements is that Medicare recipients are often discharged from a nursing home before they are ready.6

Medicare does not cover the costs of long-term stays in nursing homes.6

Medicaid may pay for nursing-home care. In all 50 states and the District of Columbia, Medicaid will pay for nursing-home care for persons who require that level of care and meet the program’s financial eligibility requirements. Be aware that the financial requirements and the level-of-care requirements vary based on the state.

Furthering the complexity is that the financial requirements change based on the marital status of the Medicaid beneficiary/applicant. For those who are eligible and meet the income and asset limits, Medicaid will pay for the complete cost of nursing-home care, including room and board. Medicaid generally requires a person exhaust most of their assets before it kicks in. Medicaid is a form of welfare—or at least that’s how it began. So to be eligible, you must become “impoverished” under the program’s guidelines.

Medicaid will cover this cost on an ongoing, long-term basis for however long that level of care is required, even if it is required for the remainder of one’s life.7

The total lifetime cost of care for someone with dementia is estimated at $392,874 in 2021.8

These costs may include:

- Medical expenses: This includes doctor’s visits, hospitalizations, and medication costs.

- Caregiving costs: Dementia patients often require round-the-clock care, which can be provided either by family members or professional caregivers. This can be a significant expense, particularly if the patient requires skilled nursing care.

- Home modifications: As the disease progresses, patients may require modifications to their home to make it safer and more accessible. These modifications can include installing handrails, wheelchair ramps, and stairlifts.

- Lost income: Caregivers may need to reduce their work hours or stop working altogether to care for their loved ones with dementia. This can result in a significant loss of income.

- Legal and financial fees: As the disease progresses, patients may become unable to manage their own affairs. This can lead to legal and financial issues that require the assistance of an attorney or financial professional.

- Hospice and end-of-life care: In the later stages of dementia, patients may require hospice or end-of-life care. These services can be expensive and may not be covered by insurance.

From a financial standpoint, obviously, we’d all love to say there are things we can do to eliminate the risk of dementia, Alzheimer’s, and mental decline. While that may not be practical, if we could postpone the age at which it occurs, it would impact this number and, beyond the number, our quality of life. If there’s anything we can do to maintain a healthy brain as long as we can, we should be interested in doing that.

Steps we can take to prepare for the potential costs of cognitive decline for ourselves or a loved one:

- Start planning early: Even if you don’t have a family history of the disease, it’s important to start thinking about the potential costs associated with it

- Consider long-term care insurance: Long-term care insurance can help cover the costs of care if you develop dementia and need assistance with daily living activities

- Consider setting up a trust: A trust can help protect your assets and ensure that they’re used to pay for your care if you develop dementia. A trust can give you greater control over how your assets are used and protected for you and your loved ones, even if you develop dementia.

- Consult with a financial professional: A financial professional can help you develop a plan to pay for the costs of dementia. They can also help you explore investment options and create a retirement plan that considers potential costs of dementia.

- Work with additional professionals: An elder law attorney can help you set up documents that may be needed, such as a durable power of attorney, trusts, a living will, and a durable power of attorney for healthcare. With a durable power of attorney, you can choose a person to make decisions on your behalf if you become unable to manage your finances independently.

A life care manager can also help provide valuable guidance on financial planning specific to cognitive decline. - Talk with your loved ones: Have open and honest conversations with your loved ones about your plans for dementia. They can provide support and help ensure that your wishes are followed.

If we can do things to keep our brains healthy, we can avoid some of the costs tied to an unhealthy brain.

Source: Hartford Funds Investor Insight

1 Renata Pellegrino et al., “A Novel BHLHE41 Variant is Associated with Short Sleep and Resistance to Sleep Deprivation in Humans,” Sleep 37, no. 8 (2014): 1327–1336, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3924.

2 Kazue Okamoto-Mizuno and Koh Mizuno, “Effects of thermal environment on sleep and circadian rhythm,” Journal of Physiological Anthropology 31, no. 14, (May 31, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1186/1880-6805-31-14.